Gambiaj;com – (BANJUL, The Gambia) – Africa’s ports are undergoing a quiet but far-reaching transformation. Once dominated by fully state-owned and state-operated models, the continent’s maritime gateways are increasingly being reshaped into complex public-private ecosystems where global capital, advanced logistics technology, and geopolitical interests converge.

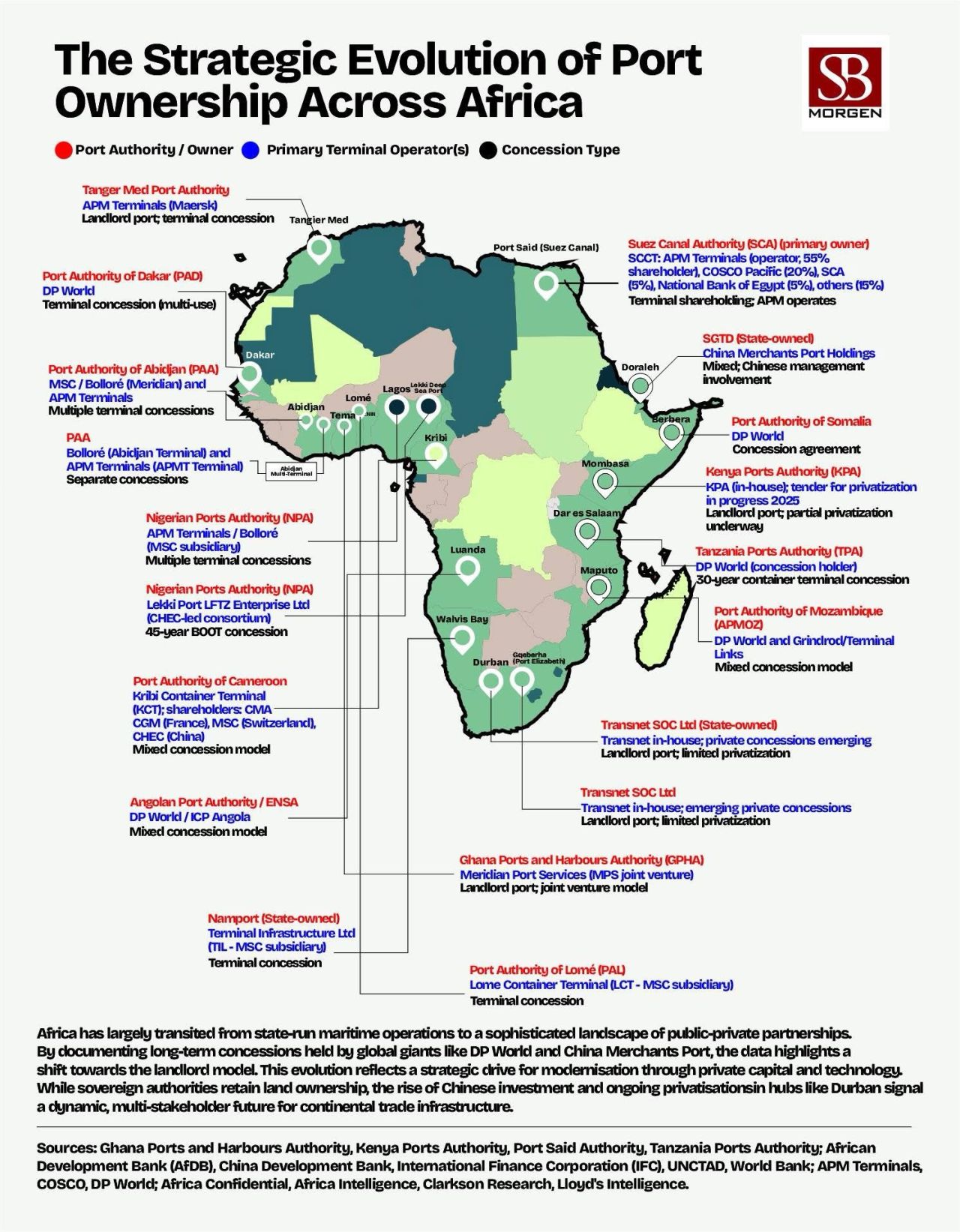

A new chart by SBM Intelligence mapping port ownership and concession structures across Africa illustrates the depth of this shift.

From Tanger Med in Morocco to Durban in South Africa, and from Lagos to Mombasa, operational control of major container terminals has steadily migrated from national port authorities to foreign and private terminal operators under long-term concession, joint-venture, and landlord-port arrangements.

Global giants such as DP World, APM Terminals (Maersk), MSC’s Terminal Investment Limited (TIL), and China Merchants Port Holdings now dominate operations across key African hubs.

While sovereign authorities typically retain ownership of port land and core infrastructure, the day-to-day management of terminals, including cranes, yard operations, and cargo handling, is increasingly outsourced to operators with the capital and technical expertise required to modernize facilities and compete in global shipping networks.

In West Africa, this model is clearly visible. Nigeria’s ports operate under multiple terminal concessions involving APM Terminals and MSC-linked Bolloré assets, while the Lekki Deep Sea Port represents a 45-year BOOT (Build-Own-Operate-Transfer) concession involving Chinese construction capital.

Ghana’s Tema Port functions as a landlord port through a joint venture between the Ghana Ports and Harbours Authority and Meridian Port Services, while Lomé’s container terminal is run by MSC subsidiary LCT.

In The Gambia, Alport (Albayrak Group) holds a 30-year concession, handling port operations and infrastructure, with a revenue-sharing agreement of 80% to Alport and 20% to the Gambian government in a 30-year Public-Private Partnership (PPP) between the Turkish Albayrak Group and the Gambia Ports Authority (GPA), operational since February 14, 2025.

North Africa reflects a similar pattern. Morocco’s Tanger Med, now one of the Mediterranean’s busiest ports, combines state ownership with terminal concessions to APM Terminals.

Egypt’s Port Said, strategically positioned along the Suez Canal, features a shareholder mix involving APM Terminals, COSCO, the Suez Canal Authority, and Egyptian financial institutions, underscoring how geopolitics, finance, and trade intersect at critical maritime chokepoints.

China’s footprint is particularly notable. From Djibouti’s Doraleh and Cameroon’s Kribi to equity stakes in terminal operations elsewhere,

Chinese firms, often backed by state lenders, have embedded themselves in Africa’s port infrastructure, typically through mixed concession models that blend commercial operations with broader strategic interests.

Southern and Eastern Africa show a slower but steady evolution. Kenya Ports Authority remains largely in-house, though partial privatization is underway.

Tanzania has granted DP World a 30-year container terminal concession at Dar es Salaam, while South Africa’s Transnet still operates as a state-owned landlord port, albeit with private concessions emerging under reform pressure.

The shift has delivered tangible efficiency gains. Private operators bring scale, automation, global shipping alliances, and financing capacity that many African states cannot mobilize alone.

Turnaround times have improved, container throughput has expanded, and several African ports are now integrated into global transshipment networks.

Yet the transformation also raises strategic questions. As operational control concentrates in the hands of a small number of multinational players, concerns over competition, pricing power, labor relations, and national sovereignty are becoming more pronounced.

Ports are no longer just logistics assets; they are strategic infrastructure tied to food security, industrial policy, energy imports, and regional trade integration under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

Analysts note that while governments retain nominal ownership, real leverage increasingly lies in concession terms, regulatory capacity, and renegotiation power, areas where many states remain institutionally weak. Financing structures, often involving foreign development banks and export credit agencies, further complicate accountability and long-term fiscal exposure.

As Africa deepens its integration into global value chains, port governance is rapidly becoming an economic and strategic policy issue rather than a purely technical one.

The cranes, containers, and terminals may symbolise efficiency and growth, but behind them lies a contested landscape where sovereignty, geopolitics, and development priorities are being quietly renegotiated along Africa’s coastlines.