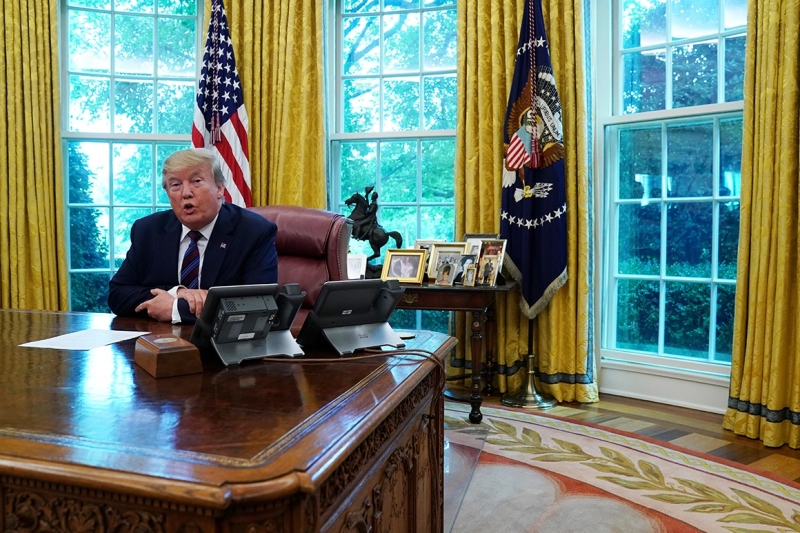

Gambiaj.com – (DAKAR, Senegal) – In a move that exposes deep contradictions in the rhetoric of African “sovereignty” and self-reliance, five African heads of state—including Senegal’s Bassirou Diomaye Faye—are set to meet President Donald Trump in Washington, D.C., today for what many analysts describe as a transactional, resource-centered summit.

Senegal’s presidency announced President Faye’s July 9-10 “working visit” to the U.S. in a terse, detail-free statement. Other confirmed participants include the presidents of Mauritania, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, and Gabon.

The summit, initially revealed by U.S. media before being confirmed by the White House, comes two months ahead of a larger U.S.-Africa summit planned for September.

The Real Agenda: Resources and Access

This mini-summit signals no grand dialogue with Africa as a continent. Rather, analysts see it as a targeted diplomatic maneuver, driven by Washington’s quest for critical resources amid intensifying global competition with China, Russia, and Turkey.

“This isn’t about Africa,” Senegalese journalist Baba Aïdara explains. “Trump is cherry-picking nations deemed strategic—whether for their minerals, their Atlantic access, or their relative political stability. It’s purely utilitarian.”

Indeed, all five invited nations have something in common: rich natural resources, valuable coastlines, or emerging oil and gas industries. Senegal, Mauritania, and Gabon are particularly notable for their oil, gas, and rare earth deposits, while Liberia and Guinea-Bissau provide strategic Atlantic access and untapped resources.

Trump, who largely ignored Africa during his first presidency and notoriously referred to African nations as “shithole countries,” now appears to have recalibrated his approach. This time, it’s about minerals, energy, and military influence.

Africa’s Minerals First, Sovereignty Later

Nicaise Mouloumbi, a prominent Gabonese civil society leader, sees the motive clearly: “Donald Trump is after rare earths, critical minerals, and timber. Gabon, for instance, has massive manganese and uranium reserves and is a potential site for a new U.S. military base in the Gulf of Guinea.”

Senegal, too, has become increasingly strategic, with its oil and gas discoveries and its status as a relatively stable democracy. Trump’s invitation to President Faye, who campaigned on “sovereignty,” is being viewed in Washington as a test of how far that sovereignty narrative can stretch under diplomatic pressure.

As Baba Aïdara puts it, Washington aims to see whether Faye’s rhetoric “is negotiable – or resistant.”

This summit throws into sharp relief the contradiction between Africa’s increasingly assertive calls for sovereignty and self-determination and the eagerness of its leaders to rush to Washington for closed-door meetings with a president openly pursuing their resources.

Many of these same African leaders have publicly criticized neocolonialism and demanded “African solutions for African problems.” Yet, their readiness to engage with Trump—known for his blunt, transactional diplomacy—suggests a more pragmatic, even opportunistic, streak behind the scenes.

“It’s pure give-and-take,” says Babacar Diagne, Senegal’s former ambassador to Washington. “Trump isn’t interested in poverty reduction or development aid like the Democrats were. His focus is trade and security—especially minerals and maritime control.”

Diagne adds that the African guests, too, are not without leverage, as their mineral wealth is now a key geopolitical bargaining chip. He warns, however, that the discussions could easily tilt in Washington’s favor if African leaders aren’t careful.

Security, Migration, and Bargaining Chips: Will African Leaders Stand Their Ground?

Beyond resource deals, security and migration are likely high on the agenda. The Gulf of Guinea is becoming a hotbed of maritime insecurity, while irregular migration from West Africa to the U.S. via Latin America is surging—particularly from Mauritania and Senegal.

Ousmane Sene, director of the West African Research Center (WARC), believes migration will inevitably surface during the talks. He highlights that thousands of young Africans from these nations have recently attempted perilous journeys to the U.S., and Trump—who has built his political brand on hardline immigration policies—will be keen to use this as leverage.

“Migration is central to Trump’s politics,” Sene warns. “It’s not just about minerals. It’s about controlling migration flows, establishing military bases, and striking deals on border controls.”

While Washington’s motives are clear, the key question is whether the African leaders will firmly defend their national interests or capitulate under U.S. pressure.

Babacar Diagne urges them to push for concessions on migration and tariffs, warning that their diaspora communities are vital lifelines for their economies. Meanwhile, Mouloumbi stresses the importance of vigilance: “It’s good to be invited by Trump, but that’s no reason to sell our countries at the first price.”

Ultimately, this mini-summit could either expose African leaders’ hollow sovereignty claims or become a rare moment of strategic assertiveness.

The choice will depend not only on what is said behind closed doors but also on whether Africa’s youthful, politically engaged populations will accept transactional deals dressed up as diplomacy.