Gambiaj.com – (BANJUL, The Gambia) – This reflection draws on Sait Matty Jaw’s recent analysis, After President Barrow’s Mamuda Speech: What Must Now Be Done on the Backway, published in The Standard. Jaw’s article usefully shifts the national conversation away from reaction and controversy toward the more demanding question of what must follow once the problem itself is no longer in dispute.

Jaw’s intervention is timely precisely because it avoids personalization and partisanship. Rather than framing the backway as a political fault line, he situates it within a broader moral and social context, reminding us that irregular migration is rarely an isolated individual choice. It is sustained by families, communities, expectations, and long-standing perceptions that have quietly taken root over time.

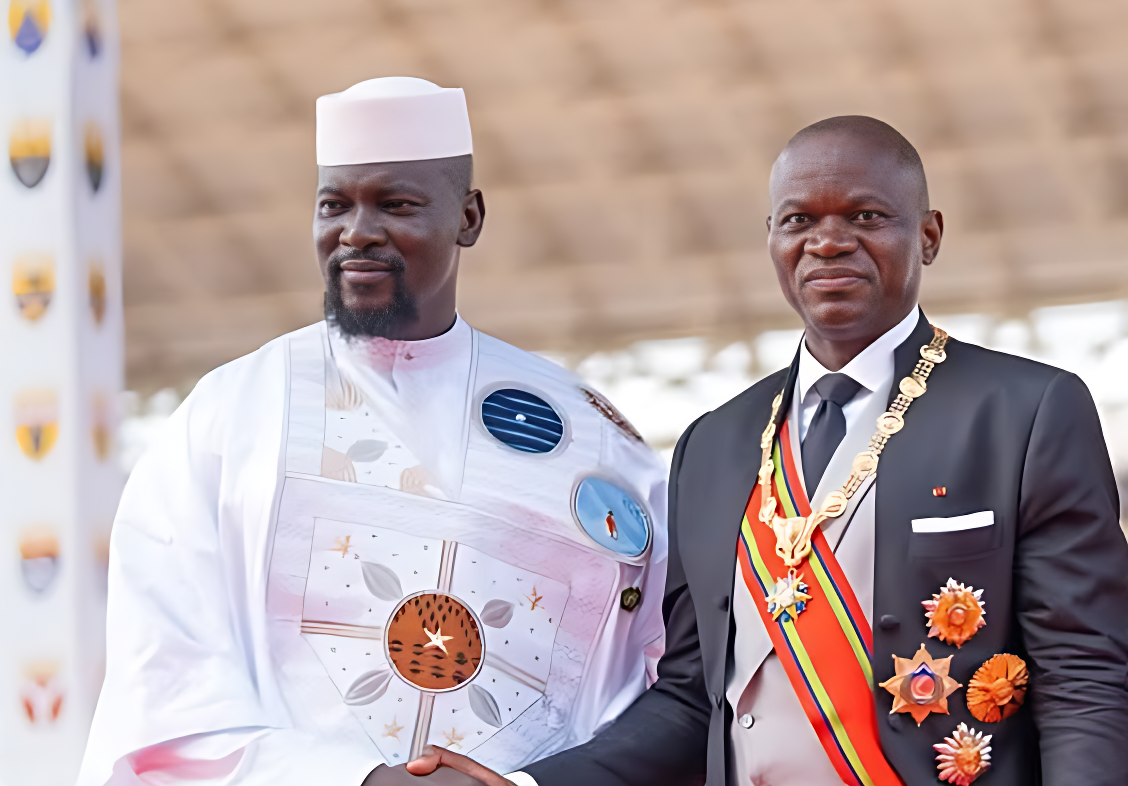

The discomfort triggered by President Adama Barrow’s Mamuda remarks should therefore not surprise us. As Jaw suggests, it reflects how deeply normalized the backway has become in our collective thinking.

Over time, what should have alarmed us has instead grown familiar—quietly tolerated, even rationalized. Naming this reality is not an act of blame; it is a necessary step toward honesty.

To understand the endurance of the backway, we must also look beyond the present moment and into history. Gambian migration did not begin with today’s perilous desert crossings or Mediterranean routes.

From the late 1950s through the late 1960s, particularly around the period of independence, many Gambians sought opportunity abroad through what were commonly referred to as stowaway journeys. Young men hid aboard cargo ships bound for Europe, driven by ambition, curiosity, and the hope of self-advancement.

These early movements occurred within a very different global context. They were not defined by today’s organized trafficking networks, nor by the scale of death and exploitation we now witness. Yet, over time, selective memory transformed those experiences into stories of courage and eventual success.

That legacy, quietly romanticized, continues to shape contemporary expectations, even as the realities of migration have grown far more brutal and unforgiving.

These inherited narratives are not abstract. They surface repeatedly in everyday conversations within families and communities. A couple of Saturdays ago, I had a long and reflective discussion with my elder siblings, Ebou and Juka, on this very issue.

What struck us most was not only the desperation of the unemployed but also the growing number of cases in which gainfully employed individuals abandon stable work to attempt the backway. This challenges the common assumption that irregular migration is driven solely by joblessness.

The explanation lies deeper than income alone. Employment that offers survival without progression, effort without reward, and patience without promise can gradually lose its meaning. In such circumstances, the backway begins to appear—falsely—as movement, escape, and opportunity. It is this perception, rather than poverty alone, that increasingly drives the decision.

Even more sensitive are cases in which parents embark on such journeys with their children. This reality demands careful understanding rather than reflexive judgment.

Many parents are influenced by distorted perceptions of life in Europe, social pressure, and the belief that opportunity exists only elsewhere. Recklessness may be present, but so too is fear—fear of stagnation, fear of being left behind, and fear of failing one’s children. Any serious response must acknowledge this complexity.

If the diagnosis is now broadly shared, the question that follows is whether it is being translated into action. Recent developments along the North Bank coast suggest an emerging, though still fragile, shift in that direction.

On the morning of January 6, 2026, security forces carried out a dawn raid in the Jinack Islands as part of a broader crackdown on irregular migration. According to a report published the same day by Alkamba Times, titled Police Launch Dawn Raid in Jinack Islands, Arrest Over 200 in Crackdown on Irregular Migration, the operation resulted in the arrest of more than 200 individuals suspected of involvement in or preparation for the backway.

Enforcement alone cannot resolve the deeper social and economic drivers of irregular migration, but such actions signal a growing recognition that dangerous normalisation must be actively disrupted.

Jaw’s article is particularly valuable because it insists that recognizing these realities is only the beginning. Agreement on the diagnosis is not enough. The more difficult task lies in translating moral clarity into sustained action—across policy, community leadership, family guidance, and public conversation.

The backway is not sustained by smugglers alone. It is sustained by myths, selective success stories, and silence about failure. Until these distortions are confronted honestly, discouragement campaigns will remain shallow and ineffective.

Viewed in this light, President Barrow’s Mamuda speech was not a dismissal of parental concern nor an abdication of state responsibility. It was an attempt, however uncomfortable, to disrupt a deadly normalization. Leadership sometimes requires speaking plainly, especially when silence risks costing lives.

The backway is more than a migration route. It is a mirror reflecting our anxieties, inherited narratives, and an unfinished social contract. If Jaw’s analysis provokes reflection and the President’s words provoke debate, then both have served a necessary purpose.

What must follow now is action—not only by government, but by society itself. Ending the backway will require courage at every level: in policy, in leadership, and in the quiet conversations held within families, like the one I shared with my siblings.

Our challenge as a society is to ensure that every child’s future is safeguarded, that families are guided wisely, and that hope is nurtured where it matters most—at home.