Gambiaj.com – (BANJUL, The Gambia) – President Adama Barrow’s latest cabinet reshuffle is more than the routine adjustment it has been presented as. Behind the bland language of “reassignments” lies a deeper strategy: the tightening of presidential control over both policymaking and oversight through the careful deployment of loyalty.

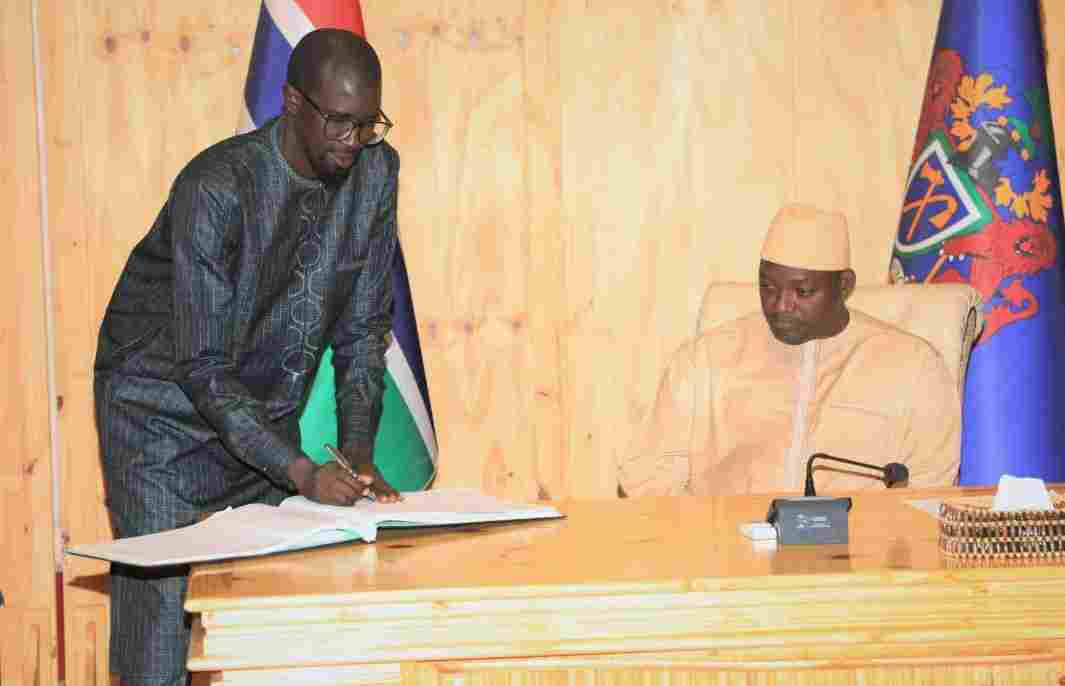

The most telling move is the redeployment of Modou Ceesay from Auditor General to Minister of Trade. Less than three years ago, Ceesay was entrusted with leading the National Audit Office and, by extension, safeguarding the independence of one of the country’s most critical accountability institutions.

Recently, Ceesay was chosen as the first chairperson of the African Professionalization Initiative’s Governing Council, a continental effort to strengthen audit and accountability.

His sudden shift into a political role does not simply deprive the audit office of its head; it reinforces the perception of the president’s ability to dictate the fortunes of those meant to scrutinize his government.

In theory, the audit office stands as a constitutional guardrail against misuse of public funds. In practice, its leadership now appears interchangeable at the president’s discretion.

This ease of replacement runs counter to the spirit of the TRRC recommendations, which emphasized building stronger firewalls around oversight bodies to shield them from political interference. By reshaping the audit hierarchy with a single decree, Barrow has shown how fragile those safeguards remain.

The reassignment of Baboucarr Ousmaila Joof to Defense illustrates the same logic in a different form. The Defence Ministry—already unsettled by frequent turnover—is a linchpin for security sector reform, one of the most sensitive and consequential undertakings of the post-Jammeh era.

By placing a trusted ally at its helm, Barrow ensures loyalty at the expense of continuity, even as reforms stall.

The thread running through these changes is unmistakable: institutional independence is weakened while presidential influence deepens.

Trusted technocrats are being converted into political loyalists, blurring the line between professional oversight and executive authority. The independence of audits, the stability of defense reform, and the coherence of trade policy all now hinge less on institutional design and more on the president’s personal network of confidence.

This is not to deny the competence of the individuals appointed. Joof, Ceesay, and Sowe each bring relevant expertise to their new roles. But competence is not the issue. The issue is independence—and the steady erosion of it.

Barrow’s reshuffle must therefore be read not just as a personnel shift, but as a test of democratic resilience.

Can the National Audit Office still act as a genuine check on government spending? Can the Defence Ministry, amid repeated turnovers, drive forward long-delayed reforms? Or will these institutions be further folded into the architecture of loyalty that now defines Barrow’s governance?

The president’s reshuffle answers one question clearly: loyalty is rewarded. What remains uncertain is whether accountability and reform will survive the bargain.