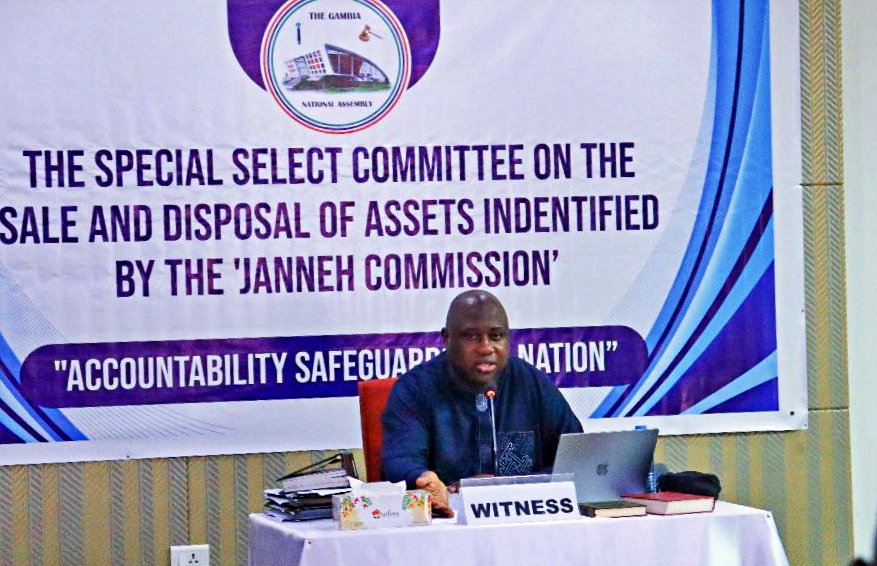

Gambiaj.com – (Banjul, The Gambia) – The Special Select Committee probing the sale and disposal of assets identified by the Janneh Commission began its public hearings Monday with a high-stakes testimony from Attorney General and Minister of Justice Dawda A. Jallow, whose appearance spotlighted the blurred boundaries between ministerial oversight, legal processes, and the independence of the Commission.

At the heart of the inquiry on day one was the legitimacy and transparency surrounding the legal and administrative foundations of the Janneh Commission—especially the Ministry of Justice’s role in hiring private counsel, deploying public assets, and managing staff attachments during the high-profile investigation into former President Yahya Jammeh’s financial dealings.

This first public session is crucial not only for setting the tone but also for potentially unlocking the accountability gaps in how one of Gambia’s most consequential post-dictatorship commissions operated.

The Janneh Commission was tasked with recovering state assets improperly acquired or misused by former President Jammeh and his associates. But as today’s testimony revealed, the way the commission itself was resourced and supported raises significant legal and ethical questions.

Core Issues Raised: Private Legal Engagement and Contractual Irregularities

A key focus was the Ministry’s decision to appoint private counsel, specifically veteran lawyer Amie Bensouda, as lead counsel for the commission. Minister Jallow defended the move as standard practice, citing the government’s regular use of private lawyers in commissions and other state affairs.

However, a deeper concern emerged: the contract was supposedly between Ms. Amie Bensouda personally and the government, yet all formal communications were sent on the letterhead of her law firm, AB & Co.

Pressed by multiple lawmakers, including Mr. Kebba Lang Fofona and Hon. Omar Jammeh, the Attorney General acknowledged the inconsistency, admitting, “It should be on her personal letterhead,” while deflecting further clarification to Ms. Bensouda herself.

This discrepancy fuels growing skepticism about procedural clarity and the potential blurring of personal and institutional interests.

Autonomy vs. Oversight: Who Really Controlled the Commission?

Another central issue was the commission’s degree of independence. While Minister Jallow maintained that the Janneh Commission was an “independent institution” in terms of its investigative mandate, he conceded that its financial and resource autonomy was limited.

Though it prepared its own work plan and budget, the commission still relied on the Ministry for essentials like transcribers, vehicles, and computers.

This dual dependency—operational independence versus logistical reliance—left the commission in a grey zone. “If total autonomy was intended,” Jallow said, “the commission would have had to seek parliamentary approval and direct funding,” acknowledging the Ministry of Justice as its de facto conduit to government resources.

Questionable Appointments and Lack of Clear Handover

Several lawmakers raised red flags about unclear terms of reference (TOR) and staffing. Hon. Suwaibou Touray criticized the absence of a formal TOR for the commission’s secretary, warning of potential duplication of duties.

Meanwhile, Hon. Jammeh expressed concern about staff receiving allowances from the commission while allegedly remaining on government payroll without appropriate qualifications or role clarity.

Minister Jallow also revealed that while there had been a “general handover” after the commission’s work concluded, no formal or specific handover was conducted for the Janneh Commission itself, raising concerns about record preservation and institutional memory.

The Livestock and Legal Grey Zones

In a notable aside, Minister Jallow touched on a court order regarding livestock confiscated by the commission.

The institution initially designated to care for the animals reportedly declined the responsibility, leaving a gap in the enforcement chain and exposing logistical vulnerabilities in asset management.

Furthermore, when Hon. Jammeh questioned whether the commission had the legal mandate to sell former President Jammeh’s assets, the Minister deferred, calling it “a loaded question.” Before he could respond, Committee Chairperson Hon. Abdoulie Ceesay intervened, reserving the issue for future deliberation.

Monday’s hearing offered more than routine administrative testimony—it exposed unresolved questions surrounding transparency, procurement, and the rule of law.

The Ministry of Justice’s facilitative role in the Janneh Commission was meant to be one of oversight and support. But the evidence shared by its current head indicates a possible lack of robust institutional protocols.

As the hearings continue, the Committee’s work may become pivotal in evaluating not only the legality of asset disposal but also the governance framework behind Gambia’s post-dictatorship truth and accountability mechanisms. At stake is the credibility of one of the Barrow administration’s most prominent efforts to restore public trust after years of autocracy.