Gambiaj.com – (Beijing, China) – Zane Li was just nine years old when the birth of his baby sister plunged his family into financial turmoil. Under China’s rigid one-child policy, his parents were fined 100,000 yuan—nearly three times their annual income—for having a second child. Now 25 and studying health services in Beijing, Li is adamant he won’t have children of his own.

“I’m not a capitalist or anything, but I don’t see a good future for my kid,” he said.

Li’s stance is emblematic of a growing generational resistance to parenthood that is complicating China’s desperate efforts to reverse its plunging birth rate.

For decades, the Chinese government penalized families for exceeding birth quotas—using fines, forced abortions, and sterilizations. Now, in a dramatic policy reversal, it is offering financial incentives to encourage more births.

Last week, China’s central government unveiled its first national childcare subsidy, offering 3,600 yuan (approximately $500) annually for each child under age three, retroactive to January 1, 2025. The program will distribute 90 billion yuan this year, aiming to benefit 20 million families. It follows years of local-level incentives that failed to stem the fertility decline.

Yet many young Chinese remain unmoved.

“The cost of raising a child is enormous, and 3,600 yuan a year is a mere drop in the bucket,” said Li, who is already burdened by student loans.

Raising a child to age 18 in China costs an average of 538,000 yuan ($75,000)—over six times the country’s GDP per capita, according to the YuWa Population Research Institute. In cities like Shanghai and Beijing, the figure can exceed 1 million yuan.

The irony of the government’s pivot—from punishing unauthorized births to pleading for more babies—is not lost on many millennials and Gen Zs. Social media has been awash with posts showing receipts of hefty fines their parents once paid for having them.

Gao, 27, was one such child. Born into a poor rural family in Guizhou province, she and her sisters were hidden from family planning authorities as their parents sought a son. Now living in Jiangsu, Gao says she has no plans to marry or have children.

“Knowing that I can’t provide a good life for a child, choosing not to have one is also an act of kindness,” she said.

Young adults like Gao and Li cite rising living costs, job insecurity, lack of work-life balance, and emotional fatigue as key reasons for their reluctance to start families.

Emma Zang, a Yale University demographer, said the new subsidy signals the government’s growing urgency about the fertility crisis—but believes it’s too little, too late.

“Young people are skeptical about the future—cash alone can’t fix that,” she said. “We’re seeing a generation opting out of parenthood not just because of cost, but because of a sense that society is no longer structured to support families.”

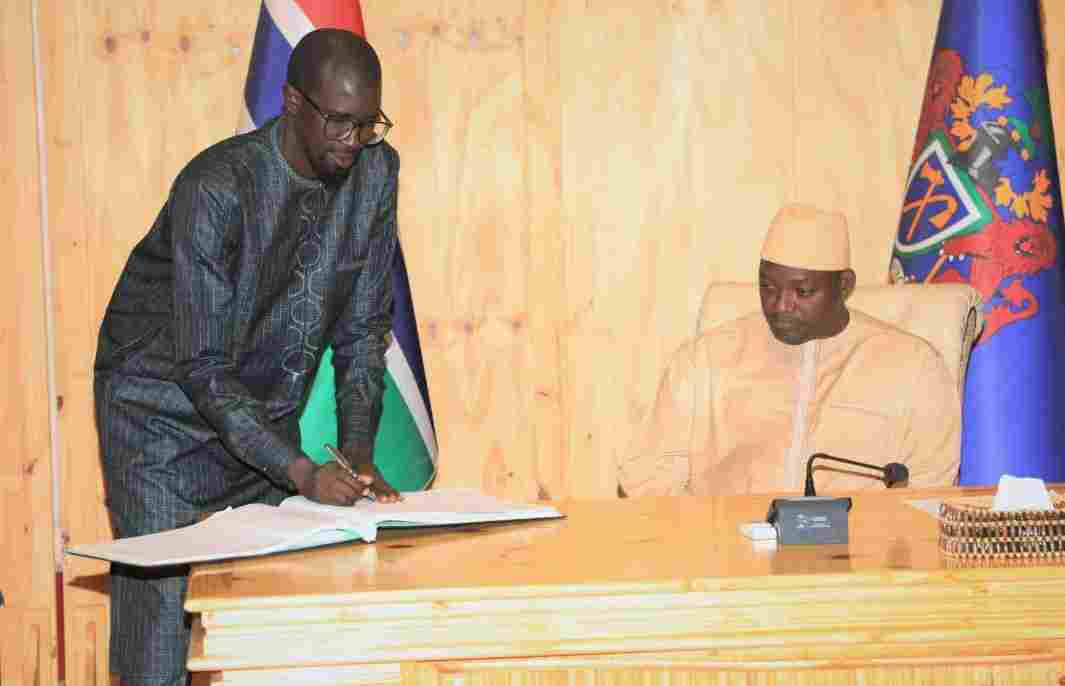

A medical worker explains local childcare subsidies at a hospital on March 16, 2025 in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia of China.

China News Service/Getty Images

The phenomenon has been labeled with buzzwords like “involution,” describing the self-defeating spiral of excessive competition, and “lying flat,” a quiet rebellion against societal expectations including marriage and childrearing.

June Zhao, 29, grew up in Beijing’s highly competitive Haidian district. Despite academic success and a stable job, she says the stress of modern life has left her disillusioned with the idea of raising a child.

“I’ve put in so much effort and received so little in return,” she said. “I can’t imagine taking on even more pressure.”

Zhao also highlights the gendered burden of parenting. “It was my mother who bore the brunt of raising me, even while working full-time. I’ve seen how hard it is for women,” she said.

Despite the policy shift, the ruling Communist Party continues to emphasize traditional gender roles, urging women to embrace their duties as “virtuous wives and good mothers.” But demographers say that narrative is out of step with the realities of modern Chinese women, who are increasingly educated and career-oriented.

“You can’t expect women to have more babies without addressing the real barriers they face—lack of paternity leave, workplace protections, and flexible jobs,” Zang said. “Right now, parenting looks like a trap. Until that changes, subsidies won’t be enough.”

After years of government pressure to have fewer children, China now finds itself in a demographic dilemma of its own making. And as it scrambles to reverse course, it must contend with a generation that sees little reward in following the rules it once enforced.