Gambiaj.com – (BANJUL, The Gambia) – The fall of Yahya Jammeh, after 22 years of authoritarian rule in The Gambia, was supposed to signal a turning point—a chance for national healing, justice, and a more equitable future. Yet, nearly a decade later, a critical question continues to haunt the country: who really benefits when a dictator falls?

Jammeh’s reign was not just about the iron grip of power—it was about a systemic plundering of national wealth, often under coercive and corrupt means. Now that wealth, once seized in the name of justice, is at the center of a bitter debate about fairness, transparency, and the enduring power of elites in a supposedly reformed Gambia.

Asset Recovery or Elite Redistribution? A Familiar Pattern of Inequality

In response to growing public discontent, the government recently issued a statement clarifying the process of recovering and disposing of Jammeh’s assets.

The Ministry of Justice outlined a two-phase approach: first, a forfeiture process led by the Janneh Commission—a Presidential Commission of Inquiry—and second, a competitive sale process overseen by a Ministerial Taskforce and managed by Alpha Kapital Advisory.

While this may sound orderly and lawful, the deeper issue lies in perception—and perhaps, in reality. These were not merely Jammeh’s personal belongings; they were assets amassed through years of exploitation of the Gambian people.

His ill-gotten wealth was extracted from a nation deprived of quality healthcare, education, and basic infrastructure. Thus, the seizure and sale of these assets should have been about restitution and rebuilding—not silent enrichment of new hands at the top.

Fatou Baldeh, founder of Women in Liberation and Leadership (WILL), has been among the most vocal critics. Her concerns go beyond legality—they strike at the moral core of the post-Jammeh transition. “As we voice our frustration over how Jammeh’s assets were distributed among a select few,” she said, “we must also be deeply outraged by the fact that a single individual wielded control over such immense wealth, likely amassed through the abuse of power as a dictator.”

Her words echo the sentiment of many Gambians who feel that the promises of Jammeh’s exit—of fairness and reform—have not translated into tangible improvements in their daily lives.

For those still battling poverty, unaffordable healthcare, and the rising costs of education, the news that Jammeh’s seized assets were sold off without clear public benefit is more than frustrating—it is a betrayal.

The Unhealed Wounds of Dictatorship Alive and Public Skepticism

What Baldeh and others remind us is that the damage of dictatorship is not limited to stolen funds. It leaves behind broken systems, entrenched inequalities, and a political class often willing to adapt and survive regardless of the regime.

The continuation of elite privilege, cloaked in the rhetoric of reform, is part of Jammeh’s lingering legacy.

The missed opportunity to use the recovered assets to directly support victims—those tortured, silenced, or made destitute during the dictatorship—is particularly painful. Many still suffer from untreated health conditions, struggle to pay school fees, or live in housing insecurity.

Their needs should have been at the forefront of any asset recovery program. Instead, they watch as the spoils of dictatorship pass into new hands, with little explanation or restitution.

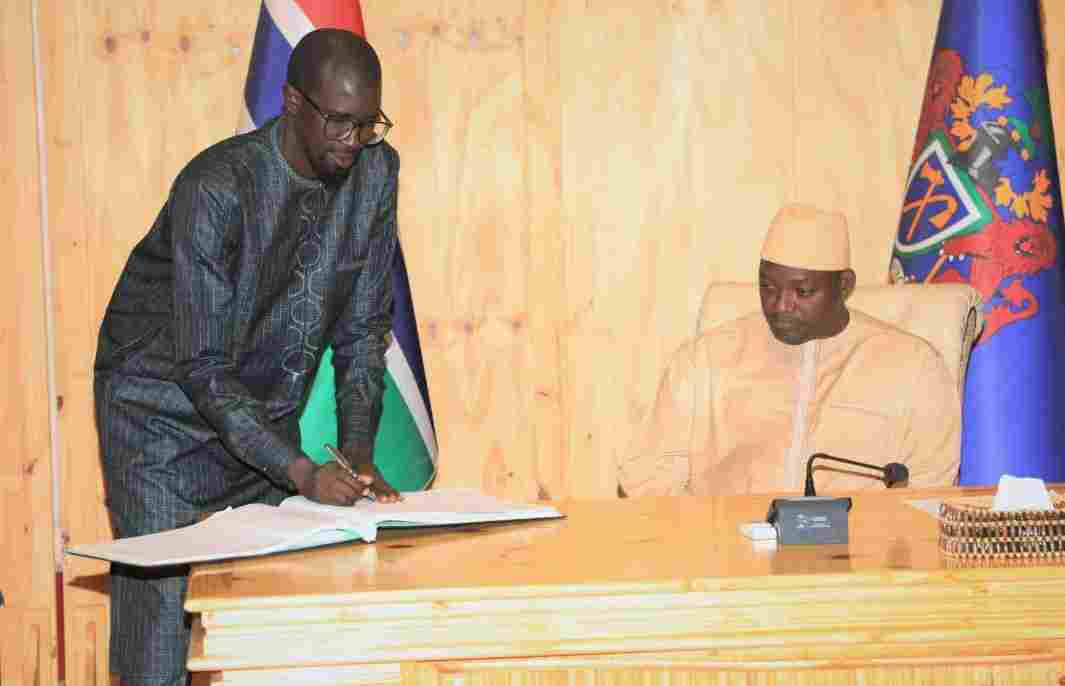

The government insists the process was transparent. Former Justice Minister Ba Tambedou, a central figure in the asset recovery efforts, strongly rejected allegations of impropriety, particularly regarding any allocation of land to his wife.

He described the accusations as inaccurate and defended his conduct as being in line with principles of accountability.

Tambedou also criticized what he described as the rushed and misleading reporting of The Republic, noting that he had attempted to clarify details, which he claims were ignored.

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Justice maintains that sales were conducted via competitive bidding, publicly advertised, and properly audited. It has pledged to release a comprehensive report detailing sale proceeds, beneficiaries, and final outcomes.

But transparency is not merely procedural. It must also be perceptible to the public. In a context where trust in institutions remains fragile, the government’s narrative is competing with a growing sense of cynicism—that the rules, however well-written, have not changed the game.

Beyond the Sale: The Struggle for True Justice as the Fight Isn’t Over

This controversy is not just about the money—it is a test of whether Gambia’s democratic transition is real or rhetorical. The handling of Jammeh’s assets has exposed a rift between the state’s self-image as a reformed democracy and the public’s lived experience of ongoing exclusion and inequality.

If the post-Jammeh era is to mean anything, it must center victims, not elites. Asset recovery should not be an exercise in economic recycling for the privileged but a vehicle for justice, reparations, and structural change.

True reform means confronting the systems that allowed a dictator to thrive—and ensuring they don’t simply survive in new guises.

Gambia’s journey away from dictatorship is far from complete. The sale of Jammeh’s assets, while legally executed, has become a symbol of a deeper failure—a failure to prioritize justice over procedure and people over politics.

The real winners after Jammeh’s fall are not supposed to be those already in power, but the many Gambians still waiting for the promise of freedom to be fulfilled.

If the government hopes to restore trust, it must go beyond reports and rebuttals. It must put victims first, ensure equity in every action, and confront the entrenched inequalities that still plague the nation. Only then can The Gambia truly turn the page on its darkest chapter—and begin writing a new one, with justice at its heart.