Gambiaj.com – (BANJUL) – The Gambia, long dependent on donor support, is at a crossroads. With key financial institutions like the IMF, World Bank, and the European Union strongly pushing for stronger domestic revenue generation, the country faces immense pressure to reduce its dependency on foreign aid. Between 2018 and 2023, donor contributions averaged 27 percent of the national budget. However, with donor support reaching its limit, the Gambian government has turned to domestic reforms to address the widening gap between development needs and available funding.

The government plans to increase the revenue-to-GDP ratio from 12 percent in 2022 to 15 percent by 2028, aiming to secure sustainable service financing and enhance public governance. But while the long-term vision is clear, the immediate consequences of these reforms are already being felt by the average Gambian.

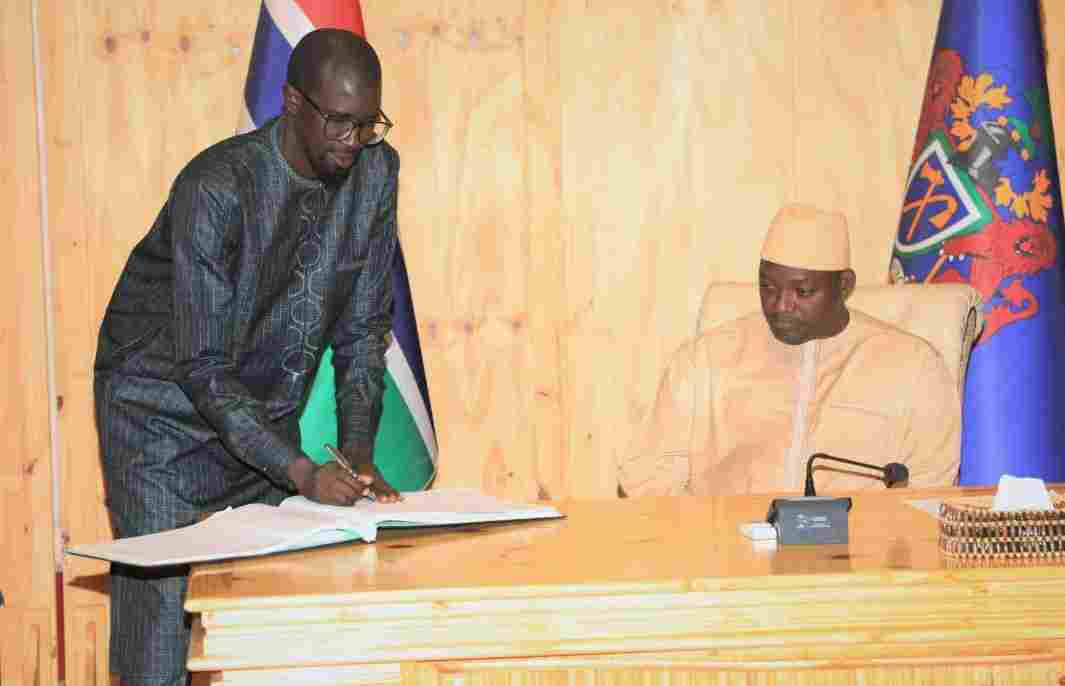

Donors and financial institutions have praised the government’s renewed efforts to increase revenue collection. With the establishment of a dedicated Directorate of Revenue and Tax, backed by technical support from the IMF and financial assistance from the EU, the government has made progress in reforming tax policies and improving compliance.

Major reforms, such as enforcing corporate income tax on public works contractors and introducing excise tax stamps on excisable goods, have already boosted revenues in 2024.

Yet, these measures come at a cost to the everyday lives of Gambians. As businesses pass on the additional tax burden to consumers, prices for goods and services have risen sharply.

With excise taxes imposed on essential commodities like petroleum, telecommunications, and tobacco, many Gambians now face higher costs for transportation, energy, and mobile services. The government’s push to tax rental properties, particularly those catering to the tourism sector, is also driving up housing costs, squeezing tenants who are already struggling in tight rental markets.

The ripple effect of these reforms extends beyond household budgets. In the corporate world, businesses targeted by the stricter tax measures have begun cutting costs, with potential reductions in employee benefits and job cuts on the horizon.

Public works contractors, faced with heavier tax obligations, may also scale back operations, delaying infrastructure projects and creating economic uncertainty for workers in the sector.

While the government insists that these reforms will lay the groundwork for future financial stability, many Gambians are frustrated with the short-term impact.

For those already living on tight budgets, higher indirect taxes like VAT and excise duties are making it harder to cover basic expenses such as food, transportation, and rent. Low-income families, in particular, are bearing the brunt of these changes, as their purchasing power diminishes in the face of rising costs.

Middle-class households are also feeling the strain, especially as children return to school and daily expenses rise. Though wealthier families may be better equipped to absorb these costs, the broader population is growing increasingly discontented with the slow pace of visible improvements in public services like healthcare and education. Many question whether the sacrifices they are making today will lead to meaningful change in the future.

At the heart of this debate is the challenge of balancing the immediate financial pressures on Gambians with the long-term benefits of economic independence.

The government, backed by its international partners, argues that reducing reliance on unpredictable foreign aid will allow for more stable and predictable financial planning. In theory, this should lead to better macroeconomic forecasts, more effective resource allocation, and improved public governance. But for now, the average Gambian sees little relief as the cost of living continues to rise.

As The Gambia presses forward with its ambitious reform agenda, it must tread carefully. The risk of political pushback from powerful corporations and interest groups is real, and reform fatigue may set in if the promised economic benefits do not materialize. Maintaining political backing for these reforms will be critical to ensuring their success.

In the meantime, the government must find ways to mitigate the short-term financial burden on its citizens. Transparency in spending, coupled with a stronger commitment to tackling corruption, will be key to restoring public trust and easing frustrations. Without tangible improvements in public services, the growing financial strain could fuel discontent and undermine the government’s reform efforts.

In conclusion, while The Gambia’s fiscal reforms are necessary for long-term sustainability, the government must address the immediate impact on its people. Striking a balance between short-term sacrifices and long-term gains will be the ultimate test of the country’s reform agenda.