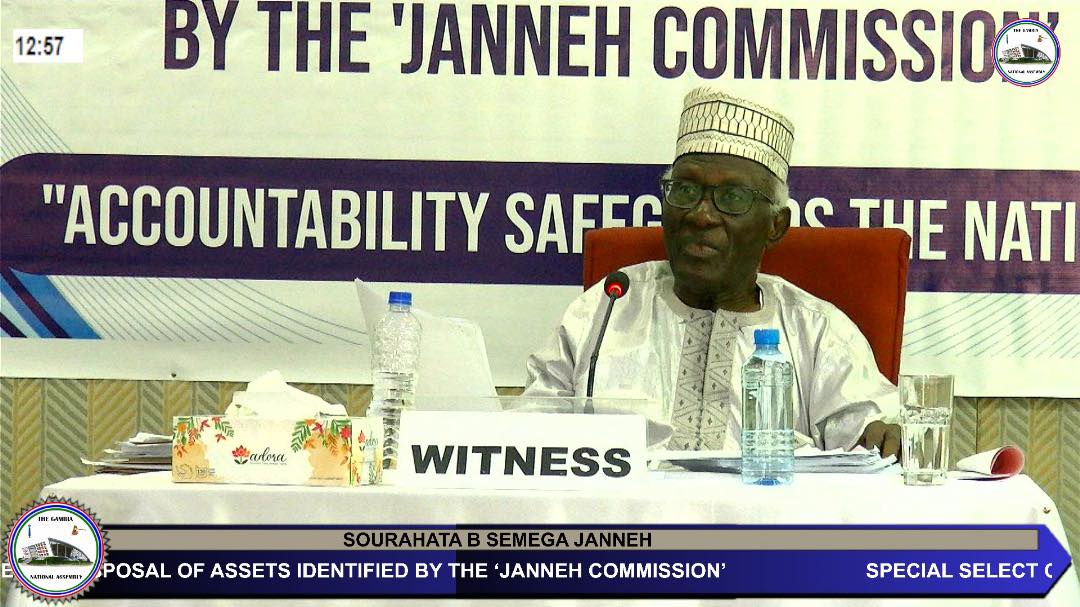

Gambiaj.com – (Banjul, The Gambia) – Surahata Janneh, former Chairperson of the Janneh Commission, has disclosed serious institutional and legal shortcomings that hampered the Commission’s operations during its mandate to probe the financial dealings of former President Yahya Jammeh and his associates.

Testifying before the National Assembly’s Special Select Committee on the Sale and Disposal of Assets Identified by the Janneh Commission, Mr. Janneh described a body that lacked key structural foundations—no dedicated legal framework, no budgetary independence, and no formal Terms of Reference (TOR) for its chair.

“We didn’t have a Commission Act. We operated under the 1903 Commission of Inquiry Act, the Constitution, and a Legal Notice,” Mr. Janneh stated. “There was no independent budget. Every expense was routed through the government.”

In contrast to the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC), which was later established with its own Act of Parliament, the Janneh Commission was governed solely by general provisions under Section 202 of the 1997 Constitution and the outdated 1903 Commission of Inquiry Act.

No TOR for Chairperson

One of the most glaring administrative gaps highlighted in the testimony was the absence of a TOR for Mr. Janneh himself.

While the other two commissioners received formal TORs attached to their appointment letters, Janneh said his own letter merely stated, “Kindly familiarize yourself with the TOR of your appointment.” No TOR was attached, nor was any special authority conferred beyond chairing duties.

He added that the Commission made decisions through consensus rather than voting, and roles were allocated based on expertise—legal, financial, and accounting—among the three commissioners.

Legal Background and Freezing Orders

Mr. Janneh also revealed that prior to the formal establishment of the Commission, he was not informed of a crucial legal move: a May 2017 interim court order obtained by the Ministry of Justice, which froze several of Jammeh’s assets and placed others under receivership.

This order, dated 22 May 2017 and referenced as MoJ 5A, was later cited as a legal foundation for the Commission’s asset investigations.

However, Mr. Janneh said he only became aware of it through documents made available to the Commission after its formation.

Mandate and Operational Limitations

According to Mr. Janneh, the Commission’s mandate was based on Clause 2 of Legal Notice No. 15 issued by the President and grounded in the Constitution.

However, no internal policy documents or operational frameworks were developed to guide day-to-day activities or coordination with external institutions, including the Ministry of Justice.

“We had several preliminary meetings with the Attorney General, but everything came down to just three documents: the Constitution, the 1903 Act, and the Legal Notice,” he said. “We had no act of our own, no separate financing structure, no staff handbook, nothing.”

He noted that while the Commission worked with law enforcement agencies and financial institutions, there were no formally documented procedures or protocols governing those relationships.

Consensus Without Structure

Despite the administrative and legal deficiencies, Mr. Janneh described the internal dynamics of the Commission as highly collaborative. Decisions were reached through dialogue and consensus, and the commissioners functioned as equals without hierarchical dominance.

Still, the absence of defined TORs, institutional autonomy, and financial independence has raised concerns over the Commission’s structural soundness and its ability to effectively manage the sensitive and high-stakes task of investigating and recovering assets estimated to be worth millions of dalasis.

The Committee’s inquiry continues as it seeks to establish accountability and transparency in the handling and disposal of recovered assets.