By Souleymane Gassama (Elgas)

In the face of the outcry raised by a proposed law authorizing female genital mutilation (FGM), the Gambian Parliament has decided to suspend discussions. A Pyrrhic victory, illustrating the impotence of legislative and political measures in countering certain challenges.

In October 2023, several researchers gathered in Geneva to discuss “conservative revolutions.” I was among them, at the invitation of the French political scientist Jean-François Bayart, along with researchers and academics from around the world—all witnesses to the bitter energy sweeping across the globe, sparing no civilizational achievement.

From Bolsonaro to Putin

The term “conservative revolutions” has gained prominence, becoming almost generic in describing the propensity of many current political movements to undermine hard-won social pacts or progress. This further underscores that progressivism is not a natural horizon blessed by time, and demonstrates that any political, geopolitical, social, or societal turbulence can unravel major human rights advances worldwide, particularly those of minorities.

The most common misuse in this regard is to consider that Europe is spared from this scourge, while the rest of the world remains a stronghold of barbarism, always ready to challenge fragile democratic gains. This overlooks the fact that whether regarding LGBT issues, the rise (or return) of conservative powers (Trump, Bolsonaro, Orban, Meloni), or the increasing role played by Putin’s Russia—which provides a model for a necessary return to certain “values”—Europe remains the epicenter of theorizing a respectable conservatism.

Feminists and the Connected

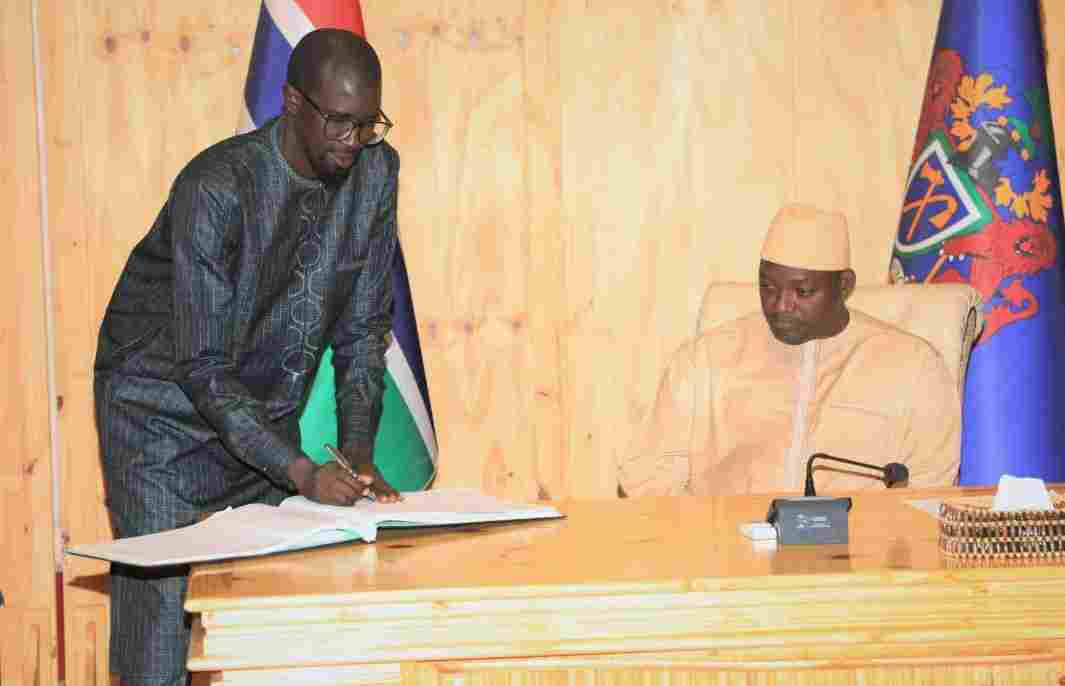

Far from these inter-Western fractures and in a Gambia grappling with social and institutional precarity, the world’s ominous energy made a stop in Banjul. A bill authorizing FGM was presented to Parliament. While there was immediate outrage and the project was ultimately shelved, the heated discussion it provoked leaves a sense of unfinished business.

In the face of massive and vociferous rejection from feminist and connected spheres, there was also, in counterpoint, an unapologetic, increasingly overt, and publicly embraced support for the project nationally. A law criminalizing FGM was passed in 2015; it was the target of this repeal project. Faced with the outcry, the project was not buried, just put on hold. A partial, minimal, and almost illusory victory, as it overlooks a reality that demonstrates the impotence of our legislative and political measures in countering certain traditional practices.

Illusory, because this bill is an outrage as it seeks to institutionalize a practice already widespread by obtaining parliamentary approval. FGM—established fact—is widely practiced in Gambia, in defiance of the law. Through clandestine channels, with the consent of populations in the name of age-old traditions, many girls are mutilated and continue to be so. They join many African women, millions, victims of this violence.

Western Interference

This observation is doubly alarming, as it seemed widely accepted that feminist struggles, legislative measures, and awareness campaigns had not put an end to this reality. It has even resurfaced, fueled by the momentum of conservative revolutions and the popularity of a discourse that opposes Western interference and directives by revitalizing the counteroffensive. Also fueled by the skillful exploitation of institutional channels to carry out coups in service of retrogressive ideas. This defeat condemns many women to face informal (and potentially formal) mechanisms that deny their most basic rights.

FGM, its specter and scepter in Gambia, go beyond the current situation. We mistake the shadow for the prey. It is a sign of a nearly consensual collective resignation to mount a battle that cannot always be postponed: winning the hearts and minds of Gambians, and not just theirs, so that the fight against FGM becomes self-evident.