By Sandy Ong and Emma Bryce

Gambiaj.com – There’s mounting evidence that heat is detrimental for pregnant women and their unborn babies. What can be done to protect them?

Edrisa Sinjanka is passionate about his work as a midwife in Keneba, a rural village in the Gambia, West Africa. “I really love my job, I love helping pregnant women in labour,” he says.

But that’s not always so easy. Frequently, women come to Sinjanka dehydrated, with cracking lips, and complaining of headaches. Pregnancy is exhausting, and some women are too fatigued to push during labour. He is noticing other worrying occurrences, too. “At times, you have women who come in with [a stillbirth] and you wonder: what is happening? Why are pregnant women having such problems?”

Sinjanka’s hunch is that Gambia’s soaring temperatures play a role in these tragedies. He’s noticed that his patients, mostly subsistence field workers who spend hours each day toiling beneath a blazing sun, have worse symptoms of heat stress during pregnancy than those who work in sheltered offices.

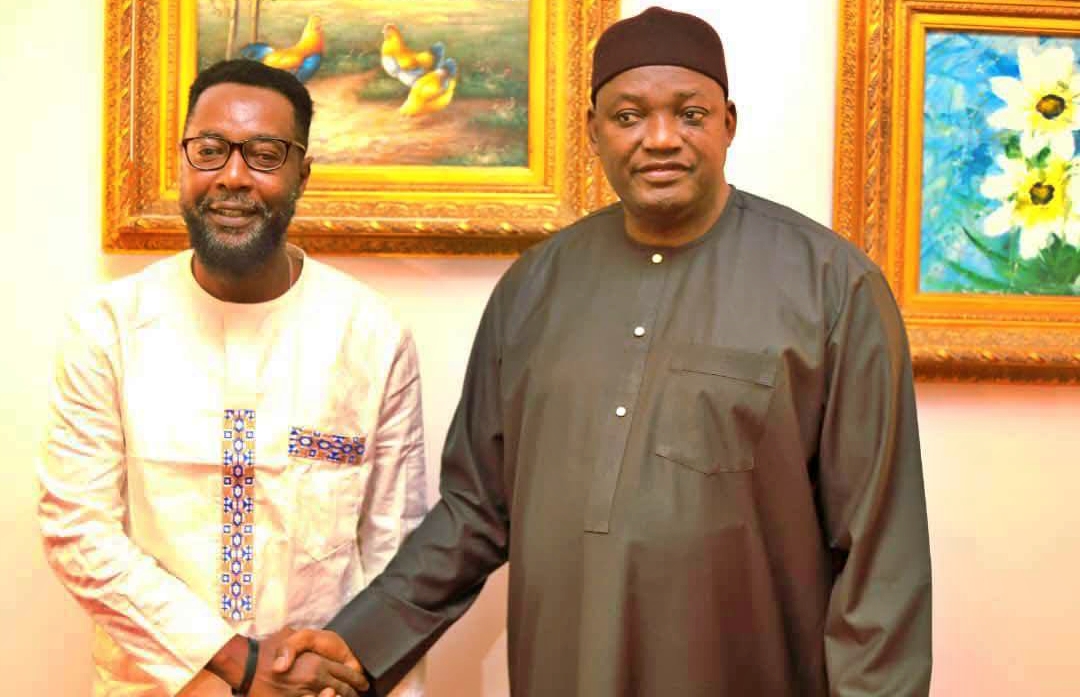

It’s a concern that led Sinjanka to join a local research project in 2019, as the on-site field coordinator in Keneba. Led by Ana Bonell, an academic clinician from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) based at its Gambia Medical Research Unit, the project aimed to understand how heat stress affects the physiology of pregnant women working as subsistence farmers, and what impact it has on their unborn children. “Subsistence farmers are often missing from occupational heat stress studies, yet they provide food for millions. And with climate change, they’re extremely vulnerable,” says Bonell.

For the study, 92 pregnant farmers in and around Keneba were examined for signs of heat stress once every two months as they went about their daily tasks. What Bonell discovered was striking: for every 1C (1.8F) rise in temperature, foetal stress – indicated by a rapid heart rate and reduced blood flow to the placenta – rose by 17%. A third of mothers experienced such symptoms.

In The Gambia, where temperatures can reach 45C (115F),and have increased by 1C (1.8F) on average over the last sixty years, that represents a significant potential risk. Such temperature extremes are being echoed worldwide, with 2023 officially the warmest year on record – although recent evidence suggests there is a 95% chance 2024 will surpass this. High heat can endanger human health, particularly in young children, the elderly, and those living with chronic health conditions. But until recently, one vulnerable group has been broadly overlooked: expectant mothers.

During pregnancy, hormonal changes and an expanding skin surface area increase one’s exposure to heat. Discomfort aside, there’s growing evidence that extreme heat can have deleterious impacts on both a mother and her unborn baby, ranging from hypertension to stillbirth.

Roughly a decade ago, publications first “started to come out suggesting that pregnant women might be at particular risk during heat waves”, says Kristie Ebi, an epidemiologist at the University of Washington in Seattle who has been studying how climate change impacts human health for 25 years. “And recently, there’s been an acceleration [in research].”

Yet the reality is that practical support for pregnant people dealing with extreme heat is still minimal today. Many nations, including the UK, don’t specifically reference pregnant women in their public heat guidance. According to the US non-governmental organisation Human Rights Watch, as of August 2020, the official heat safety web pages from US cities were more likely to mention pets in their guidance. The United Nations Population Fund – the UN’s sexual and reproductive health agency – found in one report that just 20% of the 119 countries that have made climate change pledges mention maternal and foetal health in their plans.

As global temperatures continue to soar, the question this begets is then: how quickly can research move into action, to protect pregnant women and other vulnerable populations from extreme heat?

Mounting evidence

According to Nathaniel DeNicola, an environmental health expert at the Johns Hopkins Health System in Washington DC, the evidence that we need to act is increasingly strong. Studies have linked increased heat exposure in pregnancy with a higher risk of hypertension and preeclampsia, a condition that can be fatal. Heat-stressed pregnant people are also more likely to suffer cardiac events as their due date draws near, and have a higher likelihood of developing gestational diabetes.

“There’s a lot of reasons to think that the associations we’re seeing between extreme heat and worse outcomes are connected. Like it’s not just an association, but there’s actually a biological link between them,” says DeNicola.

DeNicola notes the negative impacts heat stress can have on birth outcomes. In a 2020 review of 68 studies conducted between 2007 and 2019, which together analysed 32.7 million births in the US, DeNicola and his co-authors found a link between extreme heat and pre-term contractions, as well as premature birth. A report published this year by the World Health Organization pegs the increased risk of preterm birth at 16%. This outcome is associated with complications ranging from epilepsy to learning disabilities.

Additionally, heat exposure has been linked to higher rates of miscarriage and stillbirth. In one study that examined over 140,000 stillbirths in the US, researchers found a 10% increase in the risk of stillbirth for every 1C (1.8F) rise in temperature over a certain threshold.

“But the question is, and so what?” says Skye Wheeler, a senior researcher at the non-profit Human Rights Watch. “We’re seeing the science build on this, but that’s not enough. What interventions are we going to put in place?”

Pairing research with action

That’s the question that drives Gloria Maimela, who heads the climate and health group at the University of the Witwatersrand’s Reproductive Health HIV Institute in South Africa, a country where periods of extreme heat have been linked to significant spikes in mortality. “We’ve spent a lot of time describing the problem. Now we urgently – and I underline the word urgently – need to move to intervention research,” she says.

Maimela is currently leading two research projects in South Africa that are testing the success of various interventions in reducing heat risk in pregnant women’s lives. One she’s especially excited about is based in the northern city of Tshwane: here, a few dozen pregnant and postnatal women will be equipped with cameras to take home and record their experience of heat. They will also be asked what they “think is sensible in terms of messaging; what advice they would find acceptable to protect themselves and their unborn baby”, she says.

These testimonies will be integrated into heatwave early warning systems that are tailormade for pregnant women, which will also provide guidance on how to cope with sweltering conditions, Maimela explains. “We want to be able to say, please note that you are now exposed to extreme heat, and these are the steps that you need to take to protect yourselves,” she says.

While there are still large gaps in our knowledge about how heat impacts pregnancy, we can begin taking steps using the evidence we already have, says DeNicola. “We know enough to counsel, we know enough to act, we know enough to give some kind of proactive mitigation and even some personal adaptations”, – like avoiding outdoor work during peak heat, and staying hydrated, he adds. “It’s just a matter of that message getting through.”

But it’s not always that simple in contexts like rural Kenya, where researchers are running a project under the LSHTM’s Climate, Heat, and Maternal and Neonatal Health in Africa (CHAMNHA) consortium to, among other aims, overcome entrenched behaviours that increase women’s exposure to heat.

In sun-parched Kilifi county, women do tough subsistence work outdoors right up until birth and soon after, while wearing multiple layers of clothing during pregnancy: “It’s a cultural myth that if you show your pregnancy you will lose the baby, so they try to hide it,” says Adelaide Lusambili, a research scientist at Aga Khan University in Nairobi. Here, “heat has been normalised”, she says. Paired with rising temperatures, there is concern that this is a recipe for heat stress.

Yet even in wealthy countries in temperate regions there are huge discrepancies in heat vulnerability which are leaving some women dangerously exposed. It’s why Wheeler believes policymakers must look at the issue “through a reproductive justice lens” – not just as a problem for all pregnant people, but particularly for those who are poor and disadvantaged by racism.

To this end, Human Rights Watch is partnering with doulas who will inform low-income pregnant people on how to guard against heat in Miami-Dade, Florida. “We are kind of like ground zero when it comes to climate change and these issues,” says Esther McCant, a maternal care consultant and founder of Metro Mommy Agency, a doula service provider in the county.

In Florida, temperatures regularly hit 35C (95F) and in homes without climate control, this can be dangerous. “Families that we serve oftentimes struggle with paying for additional maintenance for their AC system, if they have one at all,” says McCant. Her company will integrate heat-awareness into training which will reach over 90 doulas in Florida, Georgia, and Hawaii into 2024 and beyond, which includes sharing practical information and support with clients.

That kind of financial and infrastructural support is important, Wheeler says. Some places are headed in the right direction, she adds, like India’s Andhra Pradesh state, which swelters in the summer. Since 2019, it has provided heat guidance targeted at pregnant women, rehydration salts on public transport, drinking water in public spaces, and even compensation for heat-related deaths.

Meanwhile, Bonell and Maimela are involved in research that could nudge policymakers elsewhere to take similarly practical steps. In a new multi-year project based in the Pakistani cities of Karachi and Matiari, Bonell is working with urban planners and architects to design community cooling-off points and housing with natural ventilation to see how well this eases the heat burden on expectant mothers. Among other interventions, Maimela is investigating the role that cash subsidies for impoverished households could play in supporting pregnant women to adapt to the heat.

For her part, Bonell is continuing to gather evidence of how extreme heat is affecting pregnant women and their unborn babies. Next, she’ll be working with more than 700 pregnant Gambian women to investigate whether there are epigenetic changes in response to shifting temperatures during different trimesters. She and her team will also take placental samples, and conduct neuro-behaviour tests in newborns, to further study the potential detrimental effects of heat on foetal development and newborn lives.

As this evidence accumulates, Sinjanka does his best to provide Keneba’s women with a comfortable, supportive labour. “I always want to put a smile on their faces at the end of the journey,” he says. Ultimately, he believes, it is research, linked to action, that will deliver this for his patients.

Story first published by bbc.com