Gambiaj.com – (BANJUL, The Gambia) – The International Centre for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), in partnership with the Alliance for Victim-Led Organisations (AVLO), has released a monitoring report assessing how victims of Jammeh-era abuses accessed services under the now-defunct Interim Medical Board.

According to the findings, the Board provided medical care to 109 victims between February and December 2024, 56 men and 49 women, across a range of specialties, including psychotherapy, eye care, and neurosurgery. Only four victims were recommended for overseas treatment due to the severity of their conditions.

The report notes that many Gambians remain unaware of the Board’s core functions, which include reviewing referrals, providing medical examinations, issuing reports, and facilitating treatment.

Despite the services offered, the ICTJ and AVLO highlight significant concerns. A majority of victims, 54 percent, reported no improvement in their health after their initial appointments.

Victims cited inadequate treatment, inability to afford prescribed medications, or inefficacy of those medications. Delays in securing appointments further undermined their well-being.

The Interim Medical Board ceased operations in November 2025. Its supervisory responsibilities, previously shared by the Health and Justice ministries, are now being transferred to the newly established Reparations Commission.

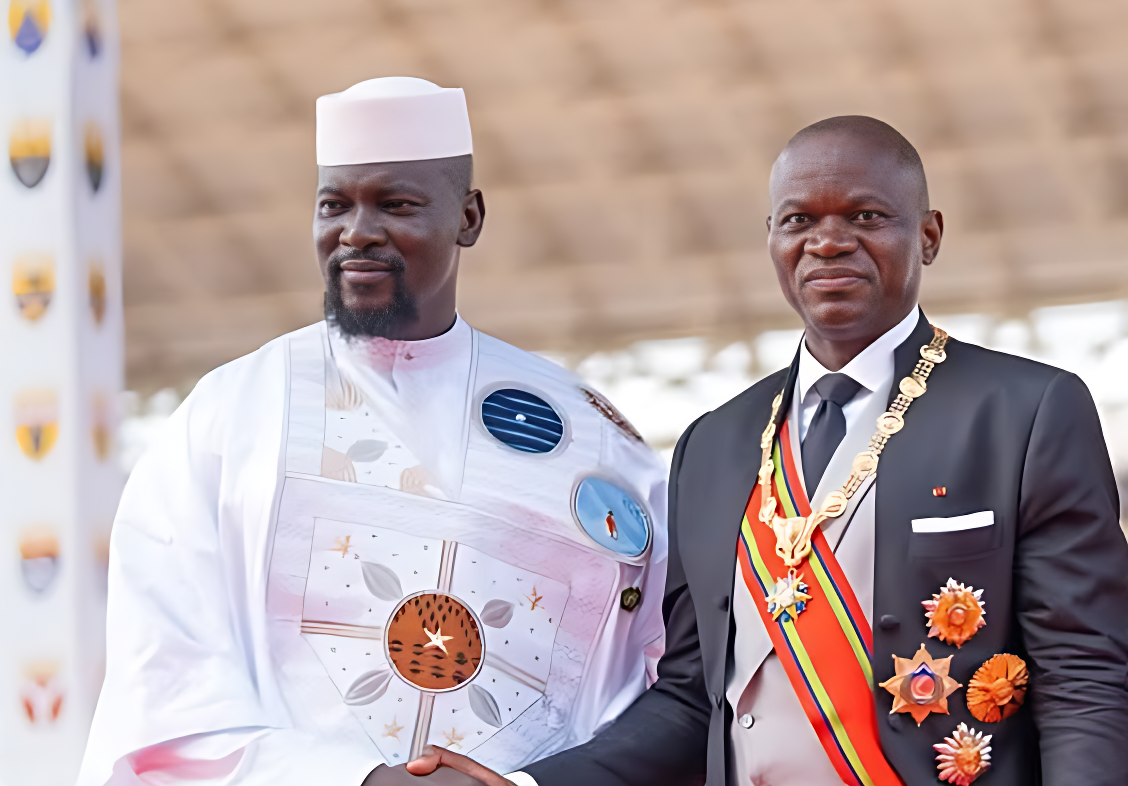

Speaking on behalf of the Commission, its chairperson welcomed the report’s publication, saying it “comes at an opportune moment… and will serve as a very useful reference material.”

He emphasized that reparations in The Gambia “must not be seen as merely compensating victims” but instead should be “transformative, restoring dignity, promoting healing, and preventing the recurrence of past atrocities.”

ICTJ representative Didier GBéry underscored the need for survivor-centered care.

“When a victim walks into a medical consultation, they are not just a patient with a physical ailment; they are a survivor carrying a history of trauma,” he said. He noted that victims deeply appreciated the empathy shown by Medical Board staff, adding, “Empathy is a form of justice. Treating a victim with dignity is, in itself, a reparative act.”

GBéry said ICTJ’s monitoring sought to determine whether the medical support system was functioning as intended: “Is the system working for the people it was built for? Are victims satisfied with the service delivered?” The findings, he added, are designed to help the Medical Board and the Reparations Commission “adjust the course” to ensure that positive intentions yield meaningful impact.

Access to services, however, remains a central challenge. Many victims reported difficulties simply reaching the Board. “It is crucial that we light the path clearly so that no victim is left unaware of the help available to them,” GBéry said, noting that logistical obstacles, such as postponed appointments and transport costs, can erode victims’ sense of dignity.

The Medical Board itself acknowledged facing constraints, particularly in communicating with the wider victim population.

While those already engaged with the process had better awareness, the report warns that this does not reflect the broader community, including victims abroad who often remained unaware of the Board’s existence. Even for those who accessed services, there was no direct contact line for queries or updates.

One victim, whose identity was withheld, questioned financial transparency: “I heard eight million dalasis was allocated to the Medical Board, but as I’m speaking, I bought some medicines and still haven’t received my refund. They always say there’s no money. Even D500 is a problem.”

Geographical barriers also loomed large. With the Board operating from Banjul, rural victims struggled to afford travel. Reimbursements, they said, were rare.

A victim from the provinces explained, “We use our own money to come to Banjul, and even with that, some of us struggle. Imagine using your last pennies for treatment, then being told to wait for reimbursement. That’s why we don’t bother. We don’t believe the government has our best interests at heart.”

Regional health facilities, the report notes, remain poorly equipped. Many lack basic diagnostic tools, experience frequent equipment breakdowns, or cannot supply essential medications, forcing victims to travel to the capital for services that should be available in their regions.

A female victim recalled spending long hours waiting to be seen by a doctor.

“Imagine coming on an empty stomach from afar and waiting from morning to 3 p.m., especially when you’re already sick. We are asking that the Medical Board be decentralized, with support from regional focal persons,” she said. She added that victims often faced costly prescriptions at private pharmacies and struggled to secure follow-up appointments.

Beyond logistical and financial constraints, the report highlights deeper emotional fatigue. Many victims feel worn down by years of participating in transitional justice processes and are reluctant to engage with yet another mechanism.

Others fear that accessing medical services could undermine their eligibility for future compensation recommended by the TRRC. Administrative obstacles also hindered those referred to private doctors or seeking treatment abroad.