Gambiaj.com – (BANJUL, Gambia) – The Gambia’s complex struggle over the legality of female genital mutilation (FGM) had taken on a deeply personal dimension with the involvement of Imam Abdoulie Fatty, a prominent religious figure advocating for the practice’s reinstatement. Imam Fatty, a cousin of The Gambia’s first convicted female genital cutter, Yassin Fatty, had emerged as a key voice in the campaign to reverse the 2015 ban on FGM.

Yassin Fatty, a 96-year-old grandmother from Bakadaji, was convicted in 2023 for performing FGM on two baby girls, making her the first person in Gambia to face legal repercussions for the practice. Her conviction ignited a widespread backlash, with some Gambians viewing the law as an imposition on their cultural and religious practices.

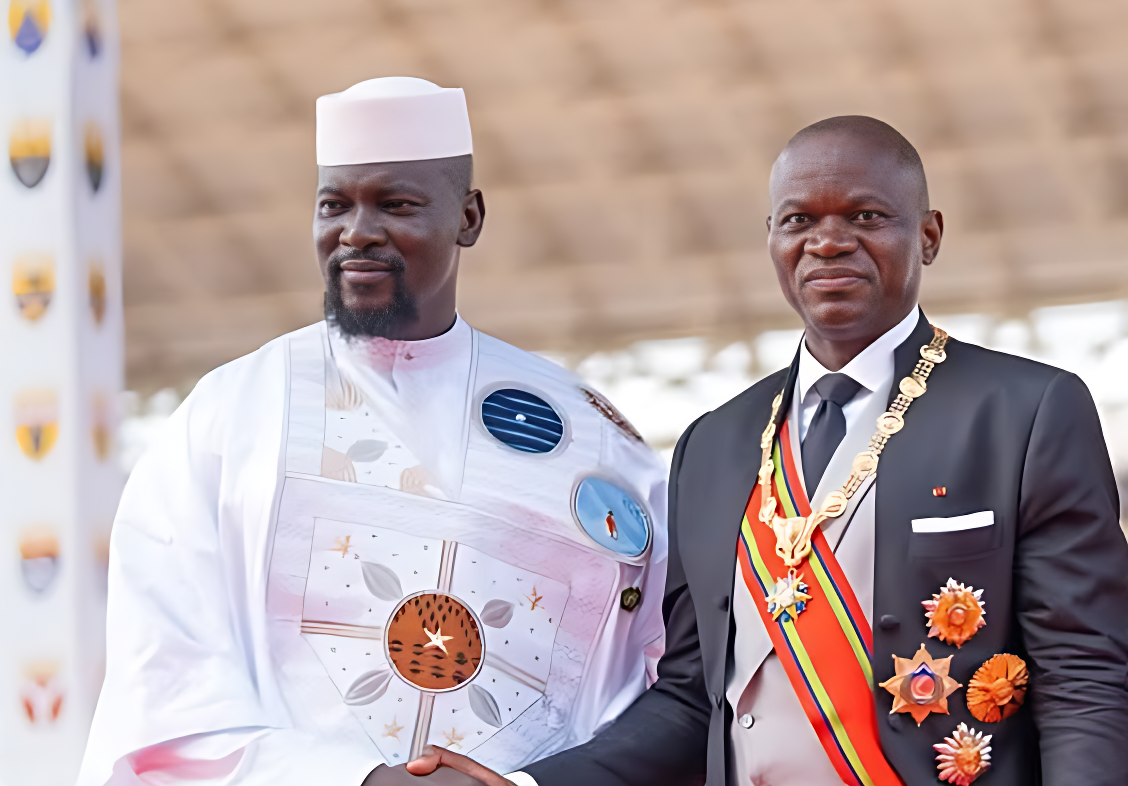

Among those leading the charge to unban FGM is her cousin, Imam Abdoulie Fatty, who argues that the ban infringes on religious freedoms and traditional values. The right of Gambians to cut girls was a cause Imam Fatty had long and loudly espoused. He falsely claimed that female genital cutting carries no health risks. He called those trying to stop it enemies of Islam. And he accused the West of imposing its culture on Gambia.

In an interview with Kerr Fatou, a Gambian online media, Imam Fatty emphasized the deeply ingrained beliefs that underpin the practice in rural communities like Bakadaji, where Yassin Fatty carried out her work for decades. “Our parents did it, and their parents before them,” he stated, echoing the sentiment of many who see FGM as a rite of passage rather than a violation of human rights.

Yassin Fatty’s conviction highlighted the ongoing tension between modern legal frameworks and traditional practices in Gambia. Despite the 2015 law, which made FGM illegal, enforcement has been sporadic, and the practice remains prevalent, particularly in rural areas where cultural norms are deeply rooted.

The New York Times, which reported extensively on the case, noted that while efforts to eradicate FGM have been supported by international organizations and local activists, the rate of cutting among Gambian girls remains alarmingly high, with 73 percent of girls aged 15 to 19 having undergone the procedure.

The case of Yassin Fatty and the subsequent involvement of Imam Abdoulie Fatty underscore the complex interplay between familial loyalty, religious belief, and cultural identity in the ongoing debate over FGM in Gambia.

Imam Fatty’s connection to the convicted cutter adds a layer of personal motivation to his public advocacy, as he seeks to protect what he views as a sacred tradition from being criminalized.

Not only Imam Fatty changed the financial fortunes of Mrs. Fatty’s family, but he visited her in Bakadaji, paid all three women’s fines, and relayed donations from some of his followers in the United Kingdom, which they used to build a cinder block wall around the back of the homestead, where Mrs. Fatty usually cut girls.

The support of such a prominent figure emboldened Mrs. Fatty. But her arrest and trial had weakened her, and though she talked a good game, her family doubted she would ever have the strength to cut again.

Critics of Imam Fatty’s campaign argue that his stance perpetuates harmful practices that have been widely condemned by medical professionals and human rights organizations. However, in communities like Bakadaji, where FGM is seen as a cornerstone of cultural identity, the push to unban the practice continues to gain momentum, fueled by influential figures like Imam Fatty.

The New York Times report further highlights the broader social and economic factors at play, with traditional practitioners of FGM, like Yassin Fatty, often relying on the practice for their livelihood and social standing. Despite the provision of alternative income sources, such as a bakery funded by anti-FGM organizations, the deep-seated beliefs surrounding the practice have proven resistant to change.

As Gambia grapples with this contentious issue, the involvement of figures like Imam Abdoulie Fatty ensures that the debate over FGM will continue to be a highly charged and deeply personal one. The question of whether cultural and religious traditions can coexist with modern legal standards remains at the heart of the national discourse, with the fate of thousands of young Gambian girls hanging in the balance.

Source: The New York Times