Pregnant women, including some Gambians, have been involved in clinical trials for Pfizer’s maternal respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine since 2019. Nevertheless, a study conducted by the British weekly peer-reviewed medical journal BMJ has shown that many of the trial participants were not informed by Pfizer about the nature of the vaccine they were vaccinated against, and that the trial of a comparable GSK vaccine was halted due to safety concerns regarding preterm birth.

The Abrysvo vaccine from Pfizer is not yet authorized in the UK, but it was recently approved for use in the US and the EU.

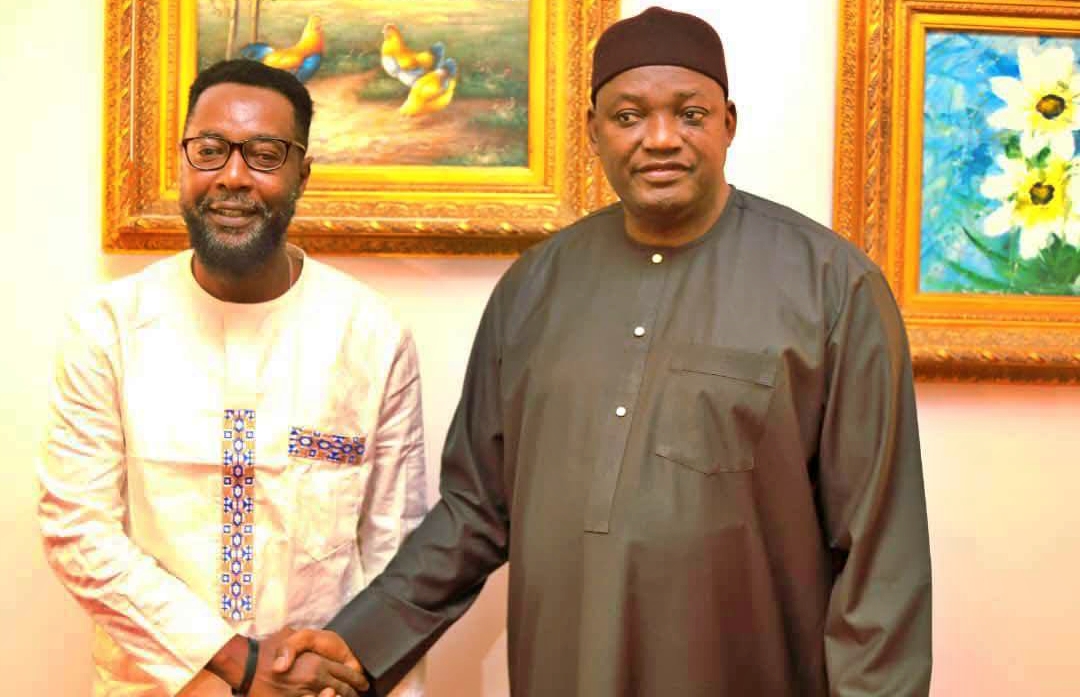

On the idea that participants ought to have been informed, other trial investigators were not in agreement. The lead author of Pfizer’s phase 3 trial report, Beate Kampmann, who oversaw a trial site in the Gambia and was the director of the Centre for Global Health at Charite University Hospital Berlin, stated that the majority of her trial participants were already receiving follow-up, so the GSK results didn’t apply to her trial participants.

Given the similarities between Pfizer and GSK’s products, one trial investigator said they asked Pfizer early in 2022 about the possible risk of preterm birth, but they were told their data hadn’t shown any increase in risk. The investigator spoke anonymously because they had signed a confidentiality agreement with the company.

Forms that The BMJ obtained from Pfizer contain contradictory language. While one section claims that the vaccine could have “life-threatening” effects on the fetus, another claims that only the expectant mother is at risk.

According to freelance investigative journalist Hristio Boytchev, some experts have criticized Pfizer for not telling participants, while others think notification would have been premature and caused needless anxiety.

Common respiratory viruses like respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) typically cause mild, cold-like symptoms, but they can also be severe, especially in young children. RSV is a major cause of infant mortality worldwide.

Recombinant RSV F protein vaccines were being developed by GSK and Pfizer to immunize expectant mothers and safeguard their unborn children.

GSK ended its phase 3 trial in February 2022 due to potential increased risk of preterm births. GSK is no longer developing its vaccine, but it is still looking into the cause, which experts believe may have nothing to do with the shot.

In its own phase 3 trial, Pfizer also investigated preterm births as an adverse event of special interest. Recently, there was a numerical (though not statistically significant) imbalance in preterm births, but there is not enough information to determine whether there is a true increase in risk or what the cause is.

Clinical trial ethicists and some vaccine researchers disagreed about whether Pfizer should have updated its consent forms or warned all of the women enrolled in the trial about the possible risk after GSK’s trial was stopped.

According to Charles Weijer, a bioethics professor at Western University in London, Canada, speaking with pregnant women involved in Pfizer’s trial about GSK’s findings would have given those who had not yet received the injection time to think about whether they still wanted to receive it, and those who had already received it the chance to seek follow-up care and additional medical advice. Weijer stated that it is unethical to withhold new and potentially significant safety information from trial participants.

Critics have also pointed to a section of Pfizer’s trial consent forms that The BMJ was able to obtain. An expert in research ethics referred to the claim that the vaccine candidate poses no risks to the fetus as “misleading” and “irresponsible.”

Pfizer did not reply to inquiries regarding informed consent from The BMJ.

Boytchev points out that different approaches have been taken by regulators in approving Abrysvo. For instance, it was only approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) if a woman was between 32 and 36 weeks pregnant. Additionally, the prescribing information included a warning about a numerical imbalance in preterm births. Pfizer is being forced by the FDA to carry out postmarketing research in order to “evaluate the indication of substantial risk of preterm birth.”

However, some organizations, like the UK’s Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunization (JCVI) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), did not think it was necessary to issue a warning about the potential risk of preterm birth or to limit the use of the vaccine to the later stages of pregnancy.

The BMJ contacted governmental health authorities in all 18 countries where Pfizer had trial sites, as well as more than 80 trial investigators, because Pfizer failed to respond to questions about whether it had informed expectant mothers in its trial about GSK’s results. None in these 18 countries responded that Pfizer had informed them.

According to credible sources, Pfizer kept enrolling and immunizing women for months after it was revealed that there may have been a preterm birth risk in GSK’s vaccine trial.

Professor Rose Bernabe of research ethics and integrity at the University of Oslo stated, “Given the benefit of hindsight, knowing what we know now, the statement in question is irresponsible and is actually factually incorrect. Besides, given the seriousness of the danger that this careless statement conceals, this deceptive statement ought to raise doubts about the legitimacy of the consent procedure.”

In April, a previous Research published in the New England Journal of Medicine in collaboration with the Medical Research Council The Gambia Unit at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (MRCG at LSHTM) said that giving the RSVpreF vaccine to women in pregnancy was effective against severe illness in infants caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

The article quoted Lead author Prof Beate Kampmann specialized in vaccinations during pregnancy to help reduce infant infections as saying: “We have no means of preventing poor outcomes from RSV in Africa, other than providing oxygen in hospitals. However, that’s a scarce resource and lack of oxygen for the infants leads to higher death rates in LMICs.”

The article in the New England Journal of Medicine did not however specify if there was an informed consent by each of the pregnant women who participated in the vaccine trial in The Gambia.