Gambiaj.com – (DAKAR, Senegal) – Eighty years ago, on December 1, 1944, a harrowing chapter in colonial history unfolded at the Thiaroye military camp near Dakar. Senegalese riflemen, former prisoners of war demanding unpaid wages, were met with brutal violence as the French army opened fire, leaving a trail of death and unanswered questions. While long ignored in France, the massacre’s legacy continues to haunt both nations as new efforts aim to confront its dark truths.

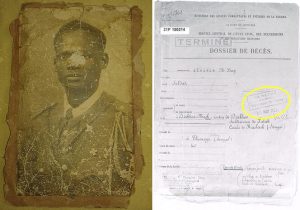

In a significant but overdue gesture, the French National Office for Combatants and War Victims officially recognized six Senegalese riflemen as “died for France” in July 2024. This acknowledgment, marking the 80th anniversary of the tragedy, followed decades of advocacy by West African families, political activists, and historians. However, many aspects of the massacre remain shrouded in ambiguity, sparking fresh debates about colonial injustice and historical accountability.

A Clash of Narratives

The Thiaroye massacre took place in the wake of World War II. Thousands of Senegalese riflemen, conscripted from French colonies, had been taken prisoner by German forces in 1940 and endured years of captivity in Europe. Returning home in late 1944, they expected back pay owed to them. Instead, they faced systemic neglect and racism.

Historians estimate that between 1,200 and 1,600 soldiers were involved in the Thiaroye protests. French military authorities labeled their demands for payment an armed rebellion, justifying the violent crackdown.

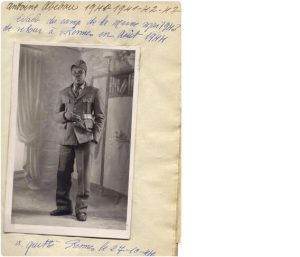

On the morning of December 1, the French soldiers opened fire on the Thiaroye riflemen. As soon as the shooting stopped, the troops arrested 48 riflemen they identified as ringleaders, including officers like Antoine Abibou, a fine scholar who escaped from a Fronstalag and was involved in the Resistance in mainland France, due to the vehemence of their protests the previous days.

Of the 48, 34 were eventually prosecuted and convicted in March 1945 to jail terms ranging from one to ten years, as well as military degradation (Antoine Abibou’s case). These offenders were granted amnesty rather than a pardon in 1946 and 1947, respectively. However, Armelle Mabon believes that amnesty leads to “oblivion.”

Survivors and their descendants, however, assert that this was a massacre fueled by colonial prejudice and an unwillingness to honor the sacrifices of African troops.

Mechanics of a Massacre

The seeds of unrest were sown during the soldiers’ journey back to Africa. In November 1944, a group of riflemen in Morlaix, France, refused to board the Circassia, the ship meant to transport them to Dakar, citing non-payment of wages. They were forcibly detained in military camps, while their comrades who complied arrived in Senegal by late November, only to face similar grievances.

On December 1, French forces unleashed automatic fire on protesting soldiers at Thiaroye. Contemporary French military reports cited 35 to 70 deaths, but historians and survivor testimonies suggest the death toll was far higher, potentially reaching into the hundreds. Discrepancies in official accounts, such as fabricated reports of mass desertions, have further fueled skepticism about the French narrative.

A Struggle for Recognition

For decades, the Thiaroye massacre was buried under layers of denial. Though the French military authorities report 35 to 70 deaths in the aftermath of the shooting (a figure taken up by the President of the Republic François Hollande during his state visit to Senegal in 2014 at the time of Thiaroye’s 70th birthday), several historians speak of several hundred deaths.

Other sources, however, such as the reports of the 34 riflemen arrested and the testimonies of the survivors gathered by their children, as well as the archives of Circassia, reveal contradictions between the various accounts of the colonial authorities and lead to criticism of the under-evaluation of the massacre.

Efforts by historians like Armelle Mabon and Martin Mourre have unearthed critical evidence, challenging colonial narratives.

Martin Mourre, for example, cites apparent contradiction in the official version. A report from the General Security in Dakar issued after December 1 describes a desertion of 400 riflemen during a 24-hour stay at Casablanca; however, a report from a squadron leader on the ship does not mention anything of the like during the Moroccan stopover, which is deemed totally usual. According to the French historian, the alleged desertion of 400 soldiers, which is “implausible for men so close to home after four years of captivity,” could have been used to conceal the true number of casualties in Thiaroye.

Survivors’ families have also fought tirelessly for justice. Biram Senghor, whose father M’Bap Senghor was among the victims, continues to demand compensation and dignity for those lost.

A Memorial Battle in the Present

The 80th anniversary of Thiaroye arrives amid shifting geopolitical dynamics in West Africa. France’s influence in the region has waned following coups in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, as well as rising calls for “memory sovereignty.” Regional leaders have drawn parallels between the forgotten sacrifices of Senegalese riflemen and broader struggles against neocolonialism.

Another point of controversy is the whereabouts of the victims’ bodies. These were most likely buried in mass graves near Thiaroye, but there are no accessible records to locate them.

This year’s recognition of the six soldiers “died for France” brings cautious hope that the massacre’s victims may finally receive proper burials, with their graves identified and honored.

Such efforts, however, remain fraught with challenges, from locating mass graves to overcoming entrenched bureaucratic hurdles.

The 80th anniversary of the tragedy revolves around this burial issue. Actually, it emphasizes how the nations of the former AOF and their former colonies have different memories of Thiaroye. Judge Martin Mourre said, “Thiaroye, remaining a wound in West Africa, has always been taken care of by political activists,” whether in the fight for independence or later to condemn the cooperation of political elites with the previous colonial force.

Legacy of Thiaroye

Thiaroye’s story continues to resonate deeply across West Africa. The success of Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène’s 1988 film Camp de Thiaroye and Senegalese President Abdoulaye Wade’s 2004 Tirailleur Day serve as examples of this.

Even now, the few living descendants of the victims are still battling for their fathers’ position to be acknowledged. In this instance, Biram Senghor and Armelle Mabon were involved in legal actions against the French government in an attempt to recover material and moral damages resulting from the murder of his father when he was only six years old.

In contrast, the Thiaroye massacre is still largely obscure in France, and the French army’s role was only recently acknowledged. Both former French presidents François Hollande and incumbent Emmanuel Macron called the Thiaroye bloodbath a “Massacre” at the hands of the French army. These admissions have been conceded to history in a completely altered regional geopolitical environment, and after the six “deaths for France” are recognized.

Eighty years on, the Thiaroye massacre remains an open wound—a stark reminder of the price of colonial exploitation and the enduring fight for justice. As history is revisited, the descendants of those who fell hope for closure, dignity, and a reckoning that transcends borders.