Banjul, The Gambia – Fresh debate has resurfaced in the oil over whether Senegal’s Sangomar oilfield extends into Gambian waters, as recent maps published by operators depict the field’s southern boundary aligning exactly with the maritime border between the two countries. The striking overlap between a geological boundary and a politically defined line has raised eyebrows among experts, who argue that the coincidence warrants closer scrutiny.

Recently published maps now show the Sangomar boundary ending precisely at the Senegal–Gambia maritime line, a coincidence that geologists say looks suspiciously neat. “It would be extraordinary for a natural subsurface reservoir to stop exactly at a politically drawn line,” Henk Kombrink, editor-in-chief of the magazine geoexpro.com noted in an article published on Wednesday.

Meanwhile, both the Gambian government and former exploration company FAR remain silent amid conflicting maps and unanswered geological questions.

Early Confidence in Gambia’s Share

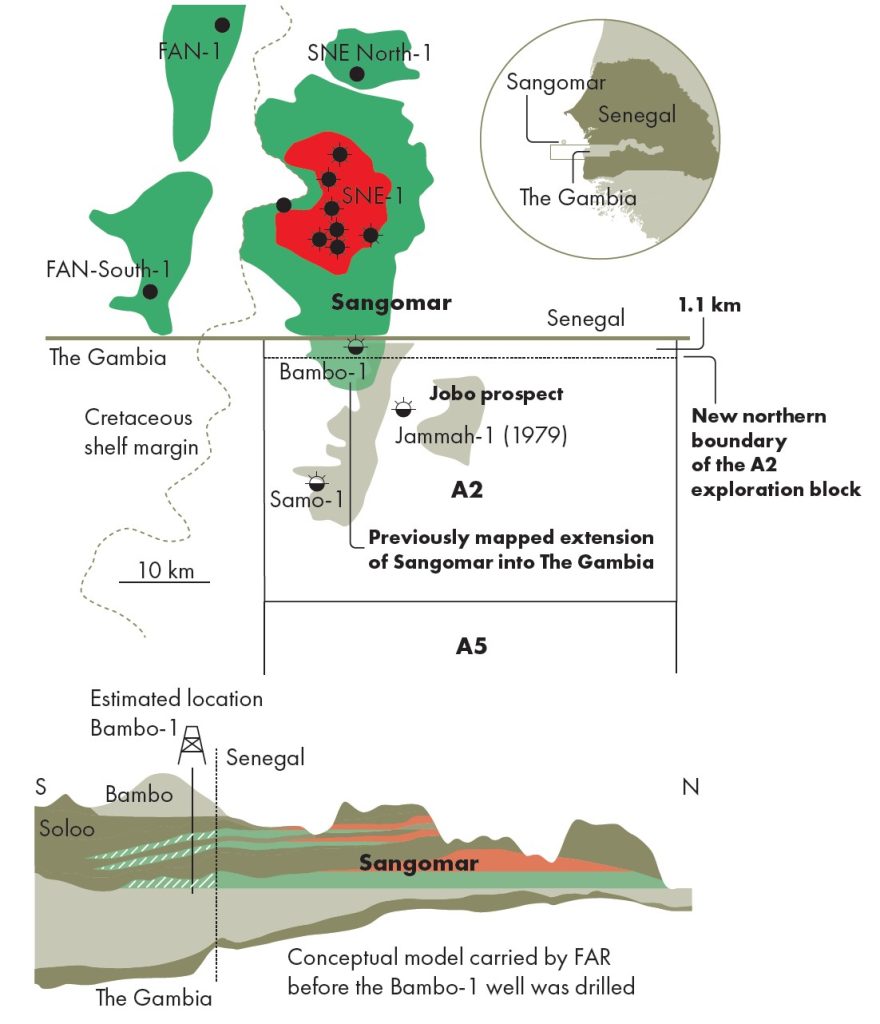

When Sangomar was first discovered in 2014, optimism in The Gambia surged. FAR Limited, the Australian explorer that held a 15% stake in the Senegalese project, acquired Gambian blocks A2 and A5 in 2017 specifically to chase what was widely seen as Sangomar’s southern extension.

Given the field’s location near The Gambia’s median line, expectations had long been high that the discovery might also unlock hydrocarbon potential for The Gambia.

At the time, FAR’s chief geologist Peter Nicholls was categorical: “Woodside and the other joint venture partners in SNE all see that the Sangomar field does extend into The Gambia. That’s not a contentious issue.”

Pre-drill presentations even suggested the Gambian blocks could host extensions of the field that might significantly increase its size.

Armed with this belief, FAR drilled two wells in Gambian waters, Samo-1 in 2018 and Bambo-1 in 2021. Both were dry. The company quickly relinquished its Gambian licenses after failing to secure new partners.

Despite FAR’s conclusions, some experts argue that one or two dry wells cannot conclusively disprove a cross-border extension of Sangomar. They note that “false negatives” are common in exploration history, with initial failures later followed by major discoveries. The UK’s Forties field is cited as a classic example, where early wells missed the main reservoir.

“The fact that Sangomar’s mapped boundary now stops exactly at the Senegal–Gambia maritime line raises serious geological questions,” Henk Kombrink observed. “It would be very peculiar if the natural reservoir facies boundary coincided so neatly with a man-made political border.”

Redrawing the Map of Shifting Block Boundaries

What has since unfolded is even more curious. In 2023, The Gambia’s government redrew the northern boundary of Block A2, shifting it more than one kilometer south.

This move placed the Bambo-1 well outside the block, leaving a thin 1.1 km strip of unlicensed water along the Senegalese border, exactly where Sangomar’s extension might have been expected.

Critics question whether this was a bureaucratic adjustment or a calculated move to separate “failed” well data from future licensing rounds. If Sangomar oil does extend into Gambian waters, this sliver of territory could prove pivotal.

Silence and Speculation Sustain a Pending Open Case.

FAR’s handling of the wells has only deepened doubts. The company released scant technical details: no well logs, no pressure data, and no porosity or permeability values. Analysts say the lack of transparency makes it impossible to independently verify the claim that poor reservoir quality ruled out Gambian potential.

Speculation is rife that FAR’s 2020 sale of its 15% stake in Sangomar, at a time when negotiations over potential unitization with The Gambia might have loomed, was part of a bigger bargain.

By stepping back quietly in Gambian waters, FAR may have smoothed the path for Woodside and its Senegalese partner Petrosen to develop Sangomar without the complications of cross-border claims.

For The Gambia, which has no commercial hydrocarbon production to date, the implications are huge. A confirmed extension of Sangomar could have delivered the country’s first oil revenues and transformed its economy.

Instead, the discovery is now celebrated in Senegal alone, with production underway and estimated resources of 560 million barrels of oil equivalent.

The unanswered question remains: Was The Gambia fairly excluded from Sangomar, or was the narrative reshaped to avoid politically messy negotiations?

Until seismic inversion results, detailed well data, and independent assessments are made public, The Gambia’s role in one of West Africa’s biggest recent discoveries remains an open, and politically sensitive case.