Gambiaj.com – (BANJUL, The Gambia) – The United Nations has warned that rising global food prices and persistent inflation are undermining the realization of the right to food, with low-income countries bearing the heaviest burden despite signs of global economic recovery.

“We all need to eat; the right to food ensures that we can do so with dignity,” said Pradeep Wagle, Chief of the Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights Section at UN Human Rights, as he underscored the growing gap between economic growth and food security outcomes.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), sustained pressures in global food markets since 2021 have driven food prices sharply upward, exposing deep structural inequalities in the global food system.

While the median global food price inflation increased from 2.3 percent in December 2020 to 13.6 percent in January 2023, low-income countries experienced far steeper spikes, with inflation peaking at 30 percent in May 2023.

FAO estimates that a 10 percent increase in food prices is associated with a 3.5 percent rise in moderate or severe food insecurity and a 1.8 percent increase in severe food insecurity. Wagle said these sustained price pressures have eroded household purchasing power, forcing families to make difficult trade-offs between food, healthcare, and education.

Rights-Based Responses to Food Insecurity

The right to food, as defined under international human rights law, guarantees every person regular, permanent, and unrestricted access to adequate, safe, and culturally acceptable food necessary for a healthy and active life. It is closely linked to other fundamental rights, including the rights to health, land, work, social security, housing and education.

UN Human Rights is advocating for a rights-based approach to tackling hunger, stressing that governments have a legal obligation to use all available resources to respect, protect, and fulfil the right to food, even during economic downturns. This includes ensuring inclusive and sustainable food systems and supporting small-scale food producers.

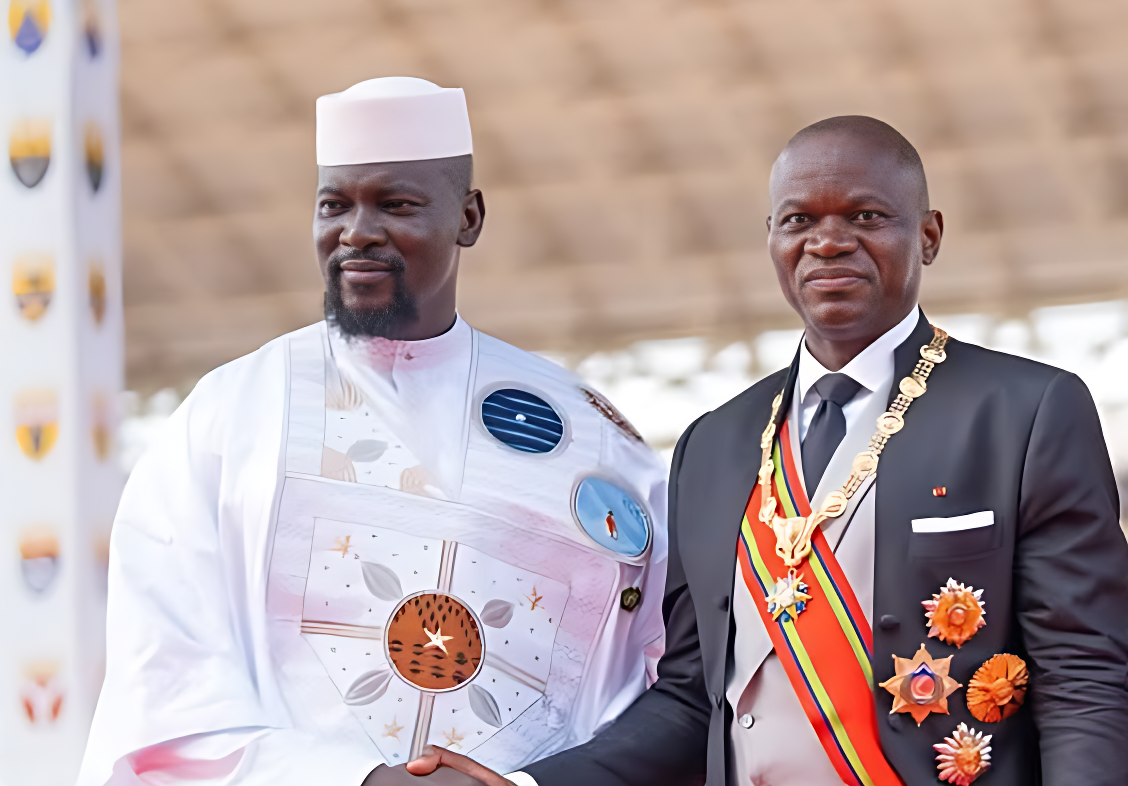

In The Gambia, these principles were central to a two-day National Dialogue on the Right to Food, co-organized this year by UN Human Rights, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) of The Gambia, and FAO. The Dialogue brought together government ministries, farmers’ associations, civil society groups, technical officials, and representatives of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights to chart a way forward through a human rights-based framework.

The discussions followed recommendations made during The Gambia’s Universal Periodic Review in January 2025, which called for stronger international cooperation, deeper engagement with human rights mechanisms, and concrete measures to enhance food security.

“There were strong recommendations made to The Gambia to implement issues relating to the right to food,” said Emmanuel Joof, Chairperson of the NHRC. “Having all these departments, ministries, and agencies be part of the process shows that the momentum is on.”

Gender Inequality and Structural Barriers

Civil society organizations and farmers’ groups used the Dialogue to highlight persistent challenges, including poor-quality or hybrid seeds, oil-polluted water sources, saline wells and boreholes, and the country’s heavy reliance on imported food and agricultural inputs.

They warned that supply chain disruptions and price spikes, coupled with limited social protection and a lack of disaggregated public data, are squeezing local producers and weakening their competitiveness.

Gender inequality also emerged as a major concern. Fatou Njie Samba of the National Women’s Farmers Organization said women, who account for between 60 and 80 percent of food production in The Gambia, continue to face systemic barriers to land ownership, finance, and decision-making. Women own just 10 percent of arable land in the country, limiting their ability to plan, invest, and adapt for long-term resilience.

FAO estimates that closing the productivity gap between farms managed by men and women could increase global agricultural value added by 3.2 percent, equivalent to USD 133.5 billion. Achieving this, the agency said, would require addressing discriminatory laws, expanding women’s access to finance and education, and tackling gender biases in land and water rights.

“The government really needs to include us more in what they are doing,” Njie Samba said. “There is still a big gap that needs to be closed, especially in decision-making.”

The Dialogue concluded with a set of recommendations intended to guide advocacy, legal reform, and budgetary decisions. These include calls for timely government support to farmers, making the right to food justiciable, and strengthening protections for related rights such as land and work.

UN Human Rights said it will follow up by providing technical support to national stakeholders, including assistance in developing right-to-food legislation, policies, and programs, and by promoting the inclusion of small-scale food producers in decision-making processes.

“At the international level, you cannot talk about human rights without the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights,” Joof said. “The support they have given to the National Human Rights Commission has translated into real impact in our society.”